_edited.jpg)

.png)

heroes that walked among us

We would love to take the time to honor our Heroes "That Walked Among Us". Remembering all of our heroes and giving them the full credit they deserve. Enjoy your time at our museum and let us know in the Virtual Village your thoughts. Thank You!

*NOTE*

UNMUTE the video to hear the audio. Thank You!

HEADWINDS - EARLY PIONEERS

click each photo below to read their story!

The birth of aviation in the United States coincided with the era of Jim Crow, a climate of formal and informal racial discrimination. African Americans — as a group — found themselves excluded from most spheres of modern technology and from this new exciting realm of aviation. One young woman from Chicago broke this barrier of racial prejudices.

Bessie Coleman became one of the first African Americans to earn a pilot's license and to seek a career in aviation. She was joined by a small but growing number of air enthusiasts who shared her dream.

Visionary William J. Powell Jr. wrote the book, Black Wings, and organized a flying club in Los Angeles. James Herman Banning established impressive records as a long-distance flyer. Cornelius Coffey forged a new center for black aviators in Chicago.

famous black mathematicians

click each photo below to read their story!

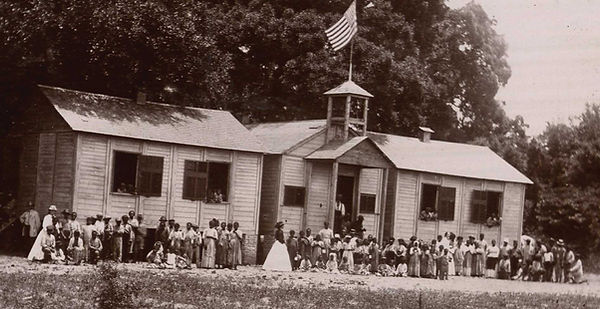

Happy Juneteenth! On June 19, 1865, enslaved African Americans in Galveston Bay, TX were notified that they, along with the more than 250,000 other enslaved black people in the state, were free by executive decree.

The contributions of African Americans throughout our nation’s history are numerous and significant. Today, we want to highlight and celebrate the Black mathematicians who have greatly impacted our nation and the future of mathematics.

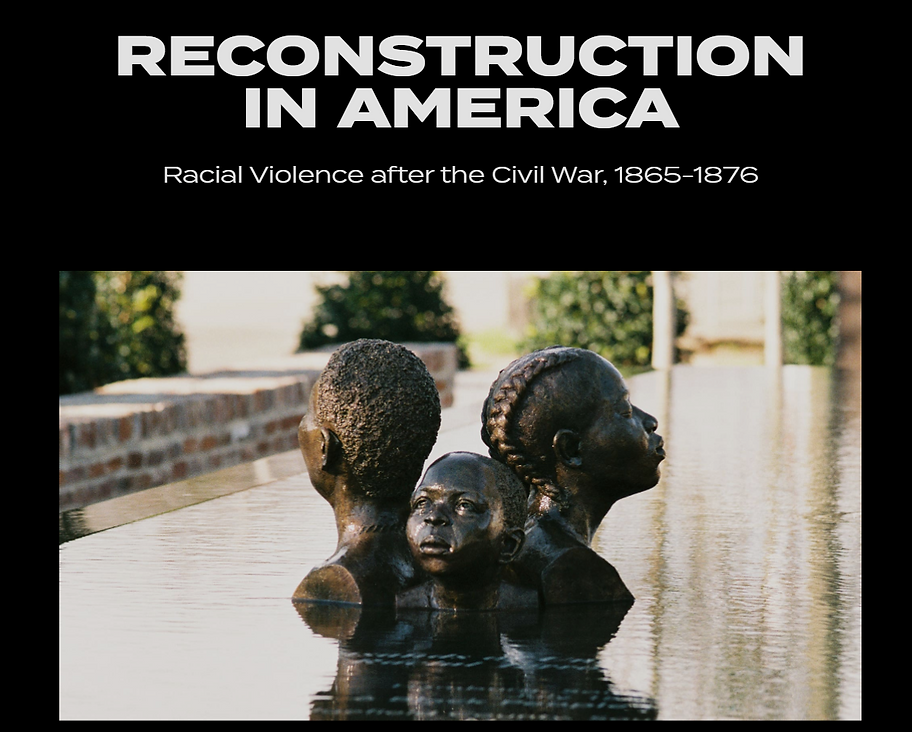

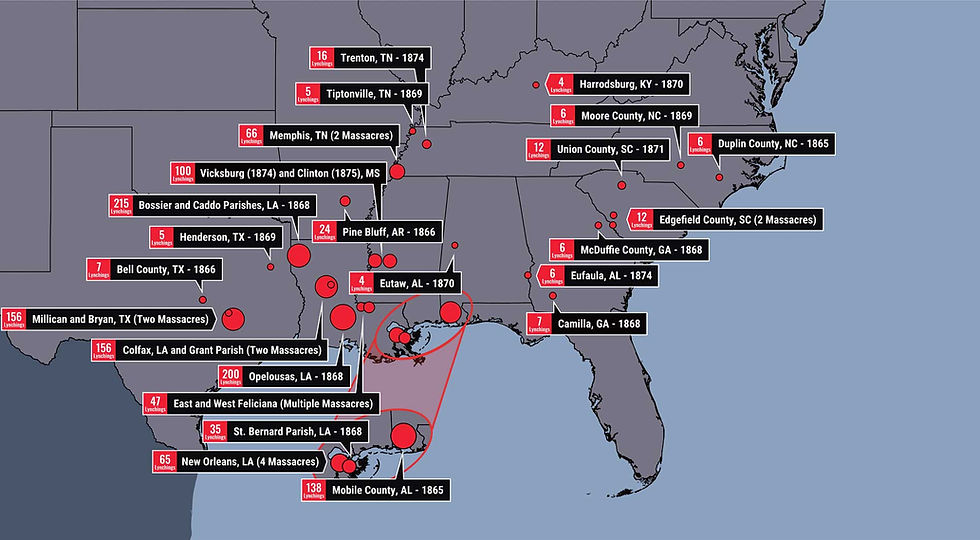

major lynchings in the united states

click each photo below to read their story!

Lynching has been a major component of racial violence in the United States since the end of the Civil War. While Americans of every racial background have been subjected to this violence, a disproportionate number of lynchings have been in the U.S. South and most of the victims were African American women, men, and children.

This page brings together a variety of information on lynchings of blacks in the U.S. It includes an overview of black lynchings by the Equal Justice Initiative titled, Lynching in America, which with its listing of over 4,000 murders, is the most comprehensive report on lynching now available. The page also includes individual descriptions of some of the most horrific lynchings, documents from the campaign to end lynching, and a bibliography of the major works on the subject.

lynching in america

Racial terror lynchings were not limited to the South, but the Southern states had the most in the nation: over 4,oo between 1877 and 1950. Click on the map to check out a Virtual Interactive map of locations, number of lynchings in the state, and information!

famous speeches

click each photo below to read their story!

If I had a thousand tongues and each tongue were a thousand thunderbolts and each thunderbolt had a thousand voices, I would use them all today to help you understand a loyal and misrepresented and misjudged people.” These were the words of Joseph C. Price, founder and President of Livingston

College in North Carolina, who in 1890 delivered an address to the National Education Association annual convention held in Minneapolis. Price’s words reflect on the long tradition of African American oratory. Listed below are some of the most significant orations by African Americans with links to the actual speeches.

primary documents

click each photo below to read their story!

The following are documents which have contributed to the shaping of African American history. These documents are a starting point for additional research and discussions that help further our understanding of the history of people of African ancestry in the United States.

Capitals of All 53 Independent African Nations

Listed below are the capitals of all 53 independent African Nations. We believe this is the only such list and historical profile of these capitals on the Internet. We have also listed the capitals of majority-black nations in Latin America and the West Indies.

nation names

Abuja, Nigeria - Accra, Ghana - Addis Abba, Ethiopia - Algiers, Algeria - Antananarivo, Madagascar

Asmera, Eritrea - Bamako, Mali - Bangui, Central African Republic

Banjul, Gambia - Bissau, Guinea-Bissau - Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo

- Bujumbura, Burundi - Cairo, Egypt - Conakry, Guinea - Dakar, Senegal

- Dar es Salaam, Tanzania - Djibouti City, Djibouti - Freetown, Sierra Leone - Gaborone, Botswana

- Harare, Zimbabwe - Juba, South Sudan - Kampala, Uganda - Khartoum, Sudan

- Kigali, Rwanda - Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo - Libreville, Gabon

- Lilongwe, Malawi - Lome, Togo - Luanda, Angola - Lusaka, Zambia

- Malabo, Equatorial Guinea - Maputo, Mozambique - Maseru, Lesotho - Mbabane, Swaziland

- Mogadishu, Somalia - Monrovia, Liberia - Moroni, Comoros - Nairobi, Kenya

- N’Djamena, Chad - Niamey, Niger - Nouakchott, Mauritania - Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

- Port Louis, Mauritius - Pretoria, South Africa - Porto Novo, Benin - Praia, Cape Verde

- Rabat, Morocco - Tripoli, Libya - Tunis, Tunisia - Victoria, Seychelles

- Windhoek, Namibia - Yamoussoukro, Cote d’Ivoire - Yaoundé, Cameroon

THE NEGRO BASEBALL LEAGUES, 1920-1950

In 1920 the Negro National League was formed by Andrew “Rube” Foster, a former player and manager for various teams. Taking advantage of the growth of the Black Northern urban populations during and following World War I, and insisting on Black ownership of the teams, Foster lead a group of team owners to create the Negro National League (NNL) in Kansas City, Missouri on February 14, 1920. The league initially had eight teams: The Chicago American Giants, the Chicago Giants, the Cuban Stars (New York), the Dayton (Ohio) Marcos, the Detroit Stars, the Indianapolis ABC’s, the Kansas City Monarchs, and the St. Louis Giants. The NNL was soon followed in 1923 by a rival league, the Eastern Colored League. Between 1924 and 1927 the two leagues met in a world series but the onset of the Great Depression in 1929 forced both leagues to fold. Teams emerged in the South as well including the Memphis Red Sox, the Birmingham Black Barons, the Atlanta Black Crackers, and the Jacksonville Red Caps.

Black professional baseball, however, continued. Between 1931 and 1937 a number of teams were formed and then disbanded. The only survivors were the teams in the new Negro National League which operated from 1933 to 1936. Black players competed abroad often on teams in Mexico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Venezuela

In 1937, two regional leagues were formed, the Negro American League in the East and the reformulated Negro National League in the West. Beginning in 1937 the winners of each league met in a world series of Black baseball. These leagues continued during World War II, but in late 1945 Jackie Robinson, who had played one season with the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro Leagues, signed a contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers organization. By 1947, after a year in the minor league, Robinson became the first Black player in Major League Baseball since 1888. After Robinson signed with the Dodgers, other (white) major league teams began signing many of the stars of the Black baseball leagues. By the end of 1950 most of the the Black professional baseball leagues had disbanded although the Indianapolis Clowns, the inspiration for the 1976 film, The Bingo Long Traveling All Stars & Motor Kings, continued playing until 1989. In all, approximately 3,400 players were part of the seven leagues operating between 1920 and 1950.

American All-Stars, 1945 on Tour in Caracas, Venezuela. Jackie Robinson, Far Left Front Row, Roy Campanella, Second From Left, Back RowDuring this centennial year, 2020, BlackPast is dedicating this page to the memory of the Negro National League and the other leagues that became Black professional baseball in the early decades of the 20th Century. We have assembled below profiles of many of the star players, the teams, and the owners. We have also added the names of often overlooked women professional baseball players of that era. If there are players, teams, or African American owners not linked here please let us know at brothersforum17@gmail.com

black teams before 1920

global african history

The following are short descriptions of the women and men who have contributed to the shaping of Global African history. These encyclopedia entries serve as a starting point for much more inclusive descriptions and discussions that appear in other sources. For additional information please consult the print or website sources cited in the entry.

RACE, CRIME, AND INCARCERATION IN THE UNITED STATES

Race, crime, and incarceration have long been linked in the United States. This page explores its various manifestations including African American participation in organized crime including in particular the rise of gangs and gang violence, African Americans and the prison system, its impact on black life, and the people and organizations engaged in challenging and changing that system. As with our pages on Black Lives Matter and Racial Violence in the United States, we are constantly updating and invite you to make suggestions on other examples that should be included. Please send them to the Heroes Museum in our Virtual Village section.

Outlaws, Gangsters, and Gangs, Old and New:

Perspectives

Perspectives on African American History features accounts and descriptions of important but little known events in African American history recalled often by those who were witnesses or participants or viewpoints about historical developments shaping the contemporary black world.

101 AFRICAN AMERICAN FIRSTS

African American history is about much more than chronicling a series of “firsts.” The time and place of a breakthrough reflects not only remarkable individual achievement but is itself an indication of the progress or lack of progress of black people in realizing the centuries-old intertwined goals of freedom, equality, and justice.

African-American Firsts: Art and Literature

African-American Firsts: Government

-

Poet: Lucy Terry, 1746.

-

Published autobiography: Briton Hammon, 1760.

-

Poet (published): Phillis Wheatley, 1773.

-

Recognized artist: Joshua Johnston, 1790, portraiture.

-

Woman’s autobiography: Jarena Lee, 1831.

-

Male Novelist: William Wells Brown, 1853.

-

Woman novelist, Harriett Wilson, 1859.

-

Recognized photographer: James Conway Farley, 1885

-

Pulitzer prize winner:Gwendolyn Brooks, 1950.

-

Pulitzer prize winner in Drama: Charles Gordone, 1970

-

Poet Laureate: Robert Hayden, 1976.

Toni Morrison Image Courtesy of Timothy Greenfied-Sanders

-

Nobel Prize for Literature winner: Toni Morrison, 1993.

-

Woman Poet Laureate: Rita Dove, 1993.

African-American Firsts: Music and Dance

-

Published musical composition: Francis Johnson, 1817.

-

Theatrical company: The African Company, 1821.

-

Nationally recognized dance performer: William Henry Lane (Master Juba), 1845.

-

Member of the New York City Opera: Todd Duncan, 1945.

-

Member of the Metropolitan Opera Company: Marian Anderson, 1955.

-

Marian Anderson

Image Ownership: Public Domain -

Male Grammy Award winner: Count Basie, 1958.

-

Woman Grammy Award winner: Ella Fitzgerald, 1958.

-

Principal dancer in a major dance company: Arthur Mitchell, 1959, New York City Ballet.

-

Officeholder in colonial America: Matthias de Souza, 1641

-

State elected official: Alexander Lucius Twilight, 1836.

-

Municipal elected official: John Mercer Langston, 1855.

-

County sheriff: Walter Burton, 1869.

-

State Supreme Court Justice: Jonathan Jasper Wright, 1870.

-

City mayor: Pierre Caliste Landry, 1868.

-

U.S. Representative: Joseph Rainey,1870.

-

U.S. Senator (appointed): Hiram Revels, 1870.

-

Governor (appointed): P.B.S. Pinchback, 1872.

-

Person to run for the presidency: George Edwin Taylor, 1904.

-

Woman legislator: Crystal Bird Fauset, 1938.

-

Woman Head of Peace Corps: Carolyn L. Robertson Payton, 1964.

-

U.S Senator (elected) Edward Brooke, 1966.

-

U.S. cabinet member: Robert C. Weaver, 1966.

-

Mayor of major city: Carl Stokes, 1967.

-

Woman U.S. Representative: Shirley Chisholm, 1969.

-

Woman cabinet officer: Patricia Harris, 1977.

-

Governor (elected): L. Douglas Wilder, 1989.

-

Woman mayor of a major U.S. city: Sharon Pratt Dixon Kelly, 1991.

-

Woman U.S. Senator: Carol Mosely Braun, 1992.

-

U.S. Secretary of State: Colin Powell, 2001.

-

Woman Secretary of State: Condoleezza Rice, 2005.

-

-

Condoleeza Rice

Image Ownership: Public Domain -

Major party nominee for President: Sen. Barack Obama, 2008.

-

U.S. President: Barack Obama, 2009.

-

Woman U.S. Attorney General: Loretta E. Lynch, 2015.

African-American Firsts: Military

-

U.S Army unit to have black men comprise more than half of its troops: 1st Rhode Island Regiment, 1778.

-

Commissioned officer in the U.S. Navy: Robert Smalls, 1863.

-

Commissioned officer above the rank of Captain in the U.S. Army: Major Martin R. Delany, 1865.

-

West Point graduate: Henry O. Flipper, 1877.

-

Graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy: Wesley A. Brown, 1949.

-

Congressional Medal of Honor winner: Sgt. William H. Carney, 1900.

-

Eugene Jacques Bullard Image Ownership: Public Domain

-

Combat pilot: Eugene Jacques Bullard, 1917.

-

General: Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., 1940.

-

Woman general: Hazel W. Johnson, 1979.

-

Woman to graduate from the U.S. Naval Academy: Janie L. Mines, 1980.

-

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: Colin Powell, 1989–1993.

-

Woman Rear Admiral in the United States Navy: Lillian Fishburne, 1998.

African-American Firsts: Science

-

Patent holder: Thomas L. Jennings, 1821.

-

Woman patent holder: Judy Reed, 1884.

-

Member of the National Academy of Sciences: David Harold Blackwell, 1965.

-

Astronaut: Robert H. Lawrence, Jr., 1967.

-

Astronaut to travel in space: Guion Bluford, 1983.

-

Head of the National Science Foundation: Walter E. Massey, 1990.

-

Woman astronaut: Mae Jemison, 1992.

-

Space Shuttle Commander: Frederick D. Gregory, 1998

African-American Firsts: Film and Theater

African-American Firsts: Law

African-American Firsts: Science

-

Published musical composition: Francis Johnson, 1817.

-

Theatrical company: The African Company, 1821.

-

Nationally recognized dance performer: William Henry Lane (Master Juba), 1845.

-

Member of the New York City Opera: Todd Duncan, 1945.

-

Member of the Metropolitan Opera Company: Marian Anderson, 1955.

-

Marian Anderson

Image Ownership: Public Domain -

Male Grammy Award winner: Count Basie, 1958.

-

Woman Grammy Award winner: Ella Fitzgerald, 1958.

-

Principal dancer in a major dance company: Arthur Mitchell, 1959, New York City Ballet.

-

Elected municipal judge: Mifflin W. Gibbs, 1873

-

Editor, Harvard Law Review: Charles Hamilton Houston, 1919.

-

Federal Judge: William Henry Hastie, 1946.

-

Woman federal judge: Constance Baker Motley, 1966.

-

U.S. Supreme Court Justice: Thurgood Marshall, 1967.

-

President of the American Bar Association: Dennis Archer, 2002.

African-American Firsts: Diplomacy

-

Hospital dedicated to black patient care: The Georgia Infirmary, 1832.

-

M.D. degree: James McCune Smith, 1837.

-

M.D. degree from a U.S. Medical School: David Jones Peck, 1847.

-

Woman to receive an M.D. degree: Rebecca Lee Crumpler, 1864.

-

Female Dental Surgeon: Ida Gray Nelson Rollins, 1890.

-

Black-owned hospital: Provident Hospital founded by Daniel Hale Williams, 1891.

-

Heart surgery pioneer: Daniel Hale Williams, 1893.

-

U.S. ambassador: Ebenezer D. Bassett, 1869.

-

Nobel Peace Prize winner: Ralph J. Bunche, 1950.

-

Woman U.S. ambassador:Patricia Harris, 1965.

-

U.S. Representative to the UN: Andrew Young, 1977.

26 Little-Known Black History Facts

From the hidden figures that made an impact, essential Black inventors, change-making civil rights leaders, award-winning authors, and show-stopping 21st century women, Black history is rich in America. and Culture, and the Library of Congress are great ways to expand on your knowledge as well as learn little-known Black history facts to further your understanding of African American culture.

literature

1. Phillis Wheatley was the first African American to publish a book of poetry, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, in 1773. Born in Gambia and sold to the Wheatley family in Boston when she was 7 years old, Wheatley was emancipated shortly after her book was released.

2. "Bars Fight," written by poet and activist Lucy Terry in 1746, was the first known poem written by a Black American. Terry was enslaved in Rhode Island as a toddler, but became free at age 26 after marrying a free Black man.

3. Clotel; or, The President’s Daughter, was the first novel published by an African American, in 1853. It was written by abolitionist and lecturer William Wells Brown.

important figures

1. William Tucker was the first known Black person to be born in the 13 colonies. He was born in Jamestown, Virginia in 1624. His parents were indentured servants and part of the first group of Africans brought to colonial soil by Great Britain.

2. Anthony Benezet, a white Quaker, abolitionist, and educator, is credited with creating the first public school for African American children in the early 1770s.

3. After graduating from Oberlin College in 1850 with a literary degree, Lucy Stanton became the first Black woman in America to earn a four-year college degree.

music and television

1. Dubbed "Hip-Hop's First Godmother" by Billboard, singer and music producer Sylvia Robinson produced the first-ever commercially successful rap record: "Rapper's Delight" by The Sugarhill Gang. And along with her husband, she co-owned the first hip-hop label, Sugar Hill Records.

2. Renowned singer and jazz pianist, Nat King Cole, was the first Black American to host a TV show: NBC's The Nat King Cole Show.

3. Stevie Wonder is not only the first Black artist to win a Grammy for Album of the Year for 1973's Innervisions, but the first and only musician to win Album Of The Year with three consecutive studio albums.

4. In 1981, Broadcast journalist Bryant Gumbel became the first Black person to host a network morning show when he joined NBC's Today Show.

5. In 1940, Hattie McDaniel became the first Black person to win an Oscar for her supporting role in Gone With the Wind. 24 years later, Sidney Poitier became the first Black man to win an Oscar for his leading role in Lilies of the Field.

14 People Who Broke Barriers to Make Black History

In honor of Black History Month, here's a look at 14 people who broke color barriers to become the first Black Americans to achieve historic accomplishments in politics, academics, aviation, entertainment and more.

click each photo below to read their story!

THE BLACK LIVES MATTER MOVEMENT

The Black Lives Matter Movement has grown into the largest black-led protest campaign since the 1960s. While specific goals and tactics vary by city and state, overall the movement seeks to bring attention to police violence against African Americans and in particular the use of deadly force against mostly unarmed civilians. While the issue of police brutality and unnecessary deadly force has been a focus point of black anger and frustration through much of the 19th and all of the 20th centuries, the violent death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin at the hands of neighborhood watch captain George Zimmerman in 2012 galvanized various efforts into a single national movement.

Due to the list of names we have branched this category out to its very own tab called "The Movement".

Click on this link here for direct access or under the Heroes Museum click the page listed, Thank You!

the incidents

(BEFORE BLM MOVEMENT WAS STARTED)

the black national anthem

Lift every voice and sing, till earth and heaven ring,

Ring with the harmonies of liberty;

Let our rejoicing rise, high as the listening skies,

Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

Sing a song full of faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of hope that the present has brought us;

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

Let us march on till victory won.

Stony the road we trod, bitter the chastening rod,

Felt in the days when hope unborn had died;

Yet with a steady beat, have not our weary feet,

Come to the place for which our fathers sighed?

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered,

We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered;

Out from the gloomy past, till now we stand at last

Where the white gleam of our star is cast.

God of our weary years, God of our silent tears,

Thou who has brought us thus far on the way;

Thou who hast by Thy might, led us into the light,

Keep us forever in the path, we pray.

Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we met Thee,

Lest our hearts, drunk with the wine of the world, we forget Thee.

Shadowed beneath Thy hand, may we forever stand,

True to our God, true to our native land.

LIFE EVERY VOICE AND SING

The Black National Anthem (1900)

Words: James Weldon Johnson

Music: John Rosamond Johnson

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY:

RESEARCH GUIDES & WEBSITES

Web research can be very useful and lead to much useful and important information. While every effort has been made to list only “reliable” sites, researchers should be aware that control of sites change (often without notice) from time to time and, thus, the reliability and point of view of the website may change (for better or worse). One of the best uses of web information is to locate good primary and secondary sources that should be directly examined. Websites also go out of existence, so, for scholarly work, they are not reliable sources, like a published work which, presumably, will always be available in some library (Library of Congress) for examination. Beware especially of quoting or otherwise relying upon unidentified opinions found on websites.

Basic guide to web research:

1. Use your library BEFORE you start your web research. You will learn many terms that will be useful in your web research. You should read at least one good, broad secondary source on the subject before starting your research.

2. Learn how to do web research. Google has a very good set of instructions. USE THEM!

3. Know the site you are using. Find out who is responsible for it. An example of a very good site is the Avalon Project at the Yale Law School (use Google to find it.)

4. Find the original printed source of the information given on the site. You may have to use your library sources or a research librarian to help you. Cite both the internet source and the printed source.

Major Research Guides and Resources

African American History

Teacher Resources

Research Resources

Black Press USA

Excellent online news service provides current national and local news articles on this website sponsored by the National Newspaper Publishers Association and the Black Press. Billed as “your independent source of news for the African American community,” the website includes links to Black Press online newspapers organized by state, a history section, press releases, and a search engine. A bit slow loading (as of 6/18/01), but highly recommended.

Ebony Online

Abstracts (not full text) of selected articles and features from current issue only. Abstracts function as a sort of expanded table of contents meant to lead the online reader to subscribe or otherwise seek out the physical magazine to continue reading the article of interest. No archived issues or articles, no search engine, no full table of contents or index.

Freedom’s Journal

Full text digitized copies of the nation’s first African American owned and operated newspaper, 1827-1829. The first 20 issues are currently (6/00) available free online, with the remaining 80 some issues scheduled to follow. Adobe Acrobat reader necessary, and available online for downloading if needed. From the State Historical Society of Wisconsin Library, a leader in the collection, preservation, and promotion of African American periodicals.

Google Cultural Institute: Black History and Culture

Google has gathered together a vast collection of more than 4,000 online primary sources including documents, photographs, and other artifacts that illustrate African American history. One document, for example, is Frederick Douglass’s handwritten 1857 letter to his former owner. Another shows the famous Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, site of the 1965 “Bloody Sunday” attack on Civil Rights marchers by Alabama State Troopers.

Legal Defense Fund (NAACP) web page

Library of Congress – Map Collections, 1500-2003

NAACP Online

Homepage of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

National Archives (Washington, D.C.)

Vibe Online

Online version of this well-known youth-oriented music and culture magazine. Loaded with graphics, advertisements, illustrations, and articles.

Western Journal of Black Studies

Online index to this well-known literary research journal; includes links to the reference sections of articles from 1977-present. Some sections are available to online subscribers only; subscriptions available to individuals for a fee. Copies of this journal, 1997-present, are available

African american events

The following are short descriptions of major events which have contributed to the shaping of Global African history. These encyclopedia entries serve as a starting point for much more inclusive descriptions and discussions that appear in other sources.

1942 BURMA ROAD RIOT, BAHAMAS

In 1942, during World War II, British military officials authorized the construction of two military air bases in the then British colony of the Bahamas. The main base would be located outside of Nassau, the colonial capital, near the airport and the other at the western end of the island of New Providence at a site called Satellite Field.

When construction began on what was locally known as “The Project,” British colonial officials announced that over 2,000 Bahamians would be employed to construct the bases. A local contractor, The Pleasantville Construction Company, was assigned to the project. It originally proposed to pay Bahamian workers eight shillings per day, the equivalent of two U.S. dollars. Local colonial officials objected and convinced the company to pay four shillings per day. Meanwhile white American workers who were imported to help build the bases were promised eight shillings.

When the local workers heard that the Americans were being paid more for the same work, they protested. When requests sent by the Bahamas Federation of Labor to the Colonial government for a pay increase were denied, workers decided to hold a protest demonstration. On June 1, 1942, thousands of Bahamian workers came to Bay Street via Burma Road in a march of solidarity. The men marched from the overwhelmingly black over-the-hill neighborhood into the Public Square in front of government offices. British Colonial Attorney General Eric Hallinan came outside to address the workers from the steps of the Colonial Secretary’s office, hoping to calm the crowd. Instead, his words turned the demonstration into a riot.

The workers headed down Bay Street in a furor, smashing windows of businesses and looting as they went along. For two days the riots ensued, and the city of Nassau was in a state of emergency. Five black Bahamian workers were killed during the riots and over thirty white men were injured. One hundred and fourteen workers were arrested for their roles in the riots and soon the local jails were filled with inmates. The Nassau jail had to stagger entry dates for the convicted to avoid overcrowding. Many of the protesters were sentenced to hard labor and some would spend almost a decade in prison for their participation in the riot. Some colonial officials promoted unsubstantiated rumors that the riot was promoted by fifth columnists in the Bahamas working in support of Nazi Germany.

In response to the protests and riot, the government offered the workers a one shilling per day increase and a free meal at lunch. This action quelled the riot as more than half of the workers returned to work by June 4th. The unintended upshot of the Burma Road Riot was the rise of the Peoples Labor Party in the Bahamas, later led by Randol Fawkes. The Peoples Labor Party organized commemorative marches to remember the Burma Road Riot. As importantly, they joined with a growing number of political activists to demand independence from Great Britain. That independence finally came thirty- one years later on July 10, 1973.

THE FIREBURN LABOR RIOT, UNITED STATES

VIRGIN ISLANDS (1878)

Chattel slavery was practiced in the Danish West Indies from around 1650 until July 3, 1848, when Colonial Governor Peter von Scholten issued an emancipation proclamation. The Danish government, however, then enacted rules that kept people enslaved by contracts for another two years. Moreover, in 1847, a year before the Governor’s decree, the government instituted a gradual emancipation plan that freed the children born to enslaved laborers from that point would be free. It further stated that all slavery would cease entirely in 1859.

Given the confusion and uncertainty around emancipation, sugar plantation owners made sure that the lives of former slaves changed little after emancipation. Many ex-slaves were hired at the plantations where they were previously enslaved and offered one-year working contracts that included a small hut, a plot of land, and a little money. Unlike during slavery, these free workers did not receive food or any care from their employers prompting some of them to declare that the new conditions were worse that enslavement.

Each October 1 (Contract Day) workers were allowed to leave their plantations and enter into contracts with new plantation owners. On October 1, 1878, workers gathered on the island of St. Croix to protest wages and the harsh living conditions they were forced to live in. This gathering turned into a riot. Participants threw stones at Danish soldiers, who soon barricaded themselves in the town Fort on the island. The riots were said to be organized and led by three women: Mary Thomas, Axeline Elizabeth Salomon, and Mathilda McBean.

On October 4, 1878, British, French, and American warships arrived at St. Croix help stop the riots but were turned away by local Danish authorities. The next day Governor von Scholten issued a declaration that all laborers should return to their plantations or be declared “rebels.” The uprising continued but after two weeks many workers had returned to their plantations and the revolt ended. During the unrest nearly 100 people were killed and 50 houses were burned. Almost 900 acres of sugar were destroyed.

The Danes arrested approximately 400 people. Twelve were sentenced to death and immediately executed. Another 39 were sentenced, but 34 had their sentences commuted to shorter terms. Among the last group were Mary, Axeline, and Mathilda who were sent to the Women’s Prison, Christianshavn, in Copenhagen, Denmark in 1882. They then returned to Christiansted, St. Croix in 1887, to serve out the remainder of their sentences. These three women became known as “The Three Queens.”

In 2004, historian Wayne James discovered historical documents that suggested the role of a fourth Queen, Susanna Abramsen, also known as Bottom Belly. St. Croix has a Queen Mary Highway in her honor, and The Three Queens fountain was commissioned by the St. Thomas Historical Trust and unveiled in 2005 on St. Thomas. Each statue holds a tool in their hands used in the revolt; a flaming torch, a sugarcane knife, and a lantern. In 2018, artist Jeanette Ehlers and La Vaughn Belle created the I Am Queen Mary monument in the port of Copenhagen. The statue is twenty-three feet tall and is Denmark’s first public monument to a black woman.

african american institutions

The following are short descriptions of the major institutions which have contributed to the shaping of African American history. These encyclopedia entries serve as a starting point for much more inclusive descriptions and discussions that appear in other sources. For additional information please consult the print or website sources cited in the entry.

THE SPINGARN MEDAL (1915- )

The Spingarn Medal is the highest honor of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Since 1915, it has been awarded annually for the highest achievement of a living African American in the preceding year or years. The twofold purpose of the award, according to the NAACP, is to call the attention of the American people to the existence of distinguished merit and achievement among Americans of African descent and to stimulate the ambition of African American youth.

The award was established in 1914 by Joel Elias Spingarn, chairman of the NAACP Board of Directors and one the organization’s first Jewish leaders, who wished, in his words, “to perpetuate the lifelong interest of my brother, Arthur B. Spingarn, of my wife, Amy E. Spingarn, and of myself in the achievements of the American Negro.” Spingarn joined the NAACP in 1913 after resigning his professorship at Columbia University over free-speech issues. He was instrumental in establishing the NAACP’s New York office, and he sponsored the award in an attempt to counter the negative depiction of Black people as criminals that was common in newspapers of the time.

The committee established to select Spingarn Medal recipients initially consisted of John Hope, president of Morehouse College, and John Hurst, bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Spingarn, who was white, insisted the awards committee include prominent white individuals so as to ensure attention would be drawn to awardees in the mainstream press. Former president William H. Taft and Oswald Garrison Villard, grandson of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, were later named to the awards committee.

The first recipient of the Spingarn Medal was Ernest E. Just, professor of biology at Howard University. The list of Spingarn awardees reads as a veritable Who’s Who of African Americans in fields such as politics, the military, medicine, arts, entertainment, and sports. Awardees include W. E. B. DuBois, George Washington Carver, Mary McLeod Bethune, Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, A. Philip Randolph, Thurgood Marshall, Ralph Bunche, Jackie Robinson, Duke Ellington, Colin Powell, and Sidney Poitier. Eleven women have won the Spingarn Medal. Two awardees received the medal posthumously. No award was made in 1938.

Upon Spingarn’s death in 1939, he left an endowment of $20,000 to enable the NAACP to continue giving the award in perpetuity. Today the awardee is selected by a nine-person committee with the presentation of the medal taking place at the NAACP’s annual convention.

MOUNT ZION UNITED METHODIST CHURCH (1816- )

Founded in 1816, Mt. Zion United Methodist Church, the oldest continuously operating African American church in Washington DC, is located at 1334 29th Street NW. The Georgetown community where the church now sits, was a central port for slave and tobacco trading in the early 1800s. At the time, one third of Georgetown’s population was Black with half enslaved and half free. The founders of Mt. Zion UMC were originally members of the Montgomery Street Church (now Dumbarton UMC) established in 1772. That church was 50% African American. In 1814, Following dissatisfaction with Montgomery Street segregation, Black members formed their own congregation called “The Meeting House.” Founders bought land on Mill Street (now 27th Street) from Henry Foxall, an officer of Montgomery Street Church. The Meeting House continued to be supervised and served by ministers of Montgomery.

The new church’s Sabbath School provided education for adults and children from 1823 to 1862. Later from 1840 and through Reconstruction, the church hosted schools sponsored by Pennsylvania Freedmen’s Relief Association and additional groups.

The name changed to “Mt. Zion Methodist Episcopal Church” in 1844 at the recommendation of Rev. Stephen Roszel, an anti-slavery leader and pastor of Montgomery. Following pushes for Black ministers to lead Black churches, in 1849 multiple Mt. Zion members left the church to start Union Wesley African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, John Wesley African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, and Ebenezer African Methodist Episcopal Church, all in the District of Columbia. Before and during the Civil War, Mt. Zion was a station on the Underground Railroad, using a vault in the Old Methodist Burying Ground to hide runaway slaves for their passage north.

The current 29th Street location of Mt. Zion Church is on land purchased by the congregation in 1875 for $2,581 from Alfred Pope, a local Black businessman and Trustee of Mt. Zion. Mt. Zion relocated to the new site in 1880, after the original church structure burned down. The first cornerstone was laid in 1876, and construction was completed in 1884 under leadership of pastors Rev. Alexander Dennis and Rev. Edgar Murphy.

By 1896, Mt. Zion church membership grew to 700 people. Construction and expansions continued with a new community center called “Community House” in 1920 on property adjacent to Mt. Zion and led by Emma Williams, a social worker.

Membership declined in the late 1930s and 1940s as the Black population of Georgetown relocated as Whites now dominated this upper income neighborhood. In the mid-1950s, however, Mt. Zion’s membership grew again as it welcomed parishioners from the wider Metro DC area through provision of a transportation service. Mt. Zion owned three buses by the mid-1960s that brought congregants from across the city and its immediate suburbs.

In 1975, Mt. Zion Church and the adjacent Mt. Zion Cemetery became Historical Landmarks on the National Register of Historical Places.

Mt. Zion’s current membership includes multi-generational families since founding, and members from the wider Washington DC area as well as the Virginia and Maryland suburbs. Few members currently live in Georgetown. Mt. Zion continues community services throughout Greater Washington and maintains active involvement in Black History and Historical Tourism.

RACIAL VIOLENCE IN THE UNITED STATES SINCE 1660

Regrettably racial violence has been a distinct part of American history since 1660. While that violence has impacted almost every ethnic and racial group in the United States, it has had a particularly horrific effect on African American life. Listed below are some of the major incidents of racial violence profiled on BlackPast.org. They range from revolts of the enslaved to more recent urban uprisings such as the Rodney King Riot in Los Angeles in 1992. This page does not cover violence affecting a single individual such as lynchings or police shootings. We are constantly updating this list but if you think other incidents should be included please send their names and a brief description to rayaustin@brothersforum.org

Revolts of the Enslaved:

New York City Slave Uprising, 1712

The Stono Rebellion, 1739

New York City Slave Conspiracy, 1741

Gabriel Prosser Revolt, 1800

Igbo Landing Mass Suicide, 1803

Andry’s Rebellion, 1811

Denmark Vesey Conspiracy, 1822

Nat Turner Revolt, 1831

Amistad Mutiny, 1839

Creole Case, 1841

Slave Revolt in the Cherokee Nation, 1842

Cincinnati Riots, 1829

Anti-Abolition Riots, 1834

Cincinnati Race Riots, 1836

The Pennsylvania Hall Fire, 1838

Christina (Pennsylvania) Riot, 1851

Detroit Race Riot, 1863

New York City Draft Riots, 1863

Memphis Riot, 1866

New Orleans Massacre, 1866

Pulaski Race Riot, 1868

Camilla Massacre, 1868

Opelousas Massacre, 1868

The Meridian Race Riot, 1871

Chicot County Race War, 1871

The Colfax Massacre, 1873

Clinton (Mississippi) Riot, 1875

Hamburg Massacre, 1876

Carroll County Courthouse Massacre, 1886

Thibodaux Massacre, 1887

New Orleans Dockworkers’ Riot, 1894-1895

Virden, Illinois Race Riot, 1898

Wilmington Race Riot, 1898

Newburg, New York Race Riot, 1899

University of Georgia Desegregation Riot, 1961

Ole Miss Riot, 1962

Houston (Texas Southern University) Riot, 1967

Orangeburg Massacre, 1968

Jackson State Killings, 1970

Antebellum Urban Violence

Civil War, Reconstruction, and Post-Reconstruction Era Violence

College Campus Violence

Race Riots, 1900-1960

Robert Charles Riot (New Orleans), 1900

New York City Race Riot, 1900

Atlanta Race Riot, 1906

Springfield, Illinois Race Riot, 1908

The Slocum Massacre, 1910

East St. Louis Race Riot, 1917

Chester, Pennsylvania Race Riot, 1917

Houston Mutiny and Race Riot, 1917

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Race Riot, 1918

Charleston (South Carolina) Riot, 1919

Longview Race Riot, 1919

Washington, D.C. Riot, 1919

Chicago Race Riot, 1919

Knoxville Race Riot, 1919

Elaine, Arkansas Riot, 1919

Tulsa Race Massacre, 1921

Rosewood Massacre, 1923

Harlem Race Riot, 1935

Beaumont Race Riot, 1943

Detroit Race Riot, 1943

Columbia Race Riot, 1946

Peekskill Riot, 1949

Cambridge, Maryland Riot, 1963

The Harlem Race Riot, 1964

Rochester Rebellion, 1964

Jersey City Uprising, 1964

Paterson, New Jersey Uprising, 1964

Elizabeth, New Jersey Uprising, 1964

Chicago (Dixmoor) Riots, 1964

Philadelphia Race Riot, 1964

Watts Rebellion (Los Angeles), 1965

Cleveland’s Hough Riots, 1966

Chicago, Illinois Uprising, 1966

The Dayton, Ohio Uprising, 1966

Hunter’s Point, San Francisco Uprising, 1966

The Nashville Race Riot, 1967

Tampa Bay Race Riot, 1967

Newark Race Riot, 1967

Plainfield, New Jersey Riot, 1967

Detroit Race Riot, 1967

Flint, Michigan Riot, 1967

Tucson Race Riot, 1967

Grand Rapids, Michigan Uprising, 1967

The King Assassination Riots, 1968

Hartford, Connecticut Riot, 1969

Asbury Park Race Riot, 1970

Camden, New Jersey Riots, 1969 and 1971

Miami (Liberty City) Riot, 1980

Crown Heights (Brooklyn) New York Riot, 1991

Rodney King Riot, 1992

West Las Vegas Riot, 1992

St. Petersburg, Florida Riot, 1996

Urban Uprisings, 1960-2000

NATIONAL AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC LANDMARKS BY STATE

Since the beginning of the 20th Century, the U.S. Government and most states have identified landmarks associated with African American history. Listed below are the African American National Historic Landmarks by state, as certified by the National Park Service’s National Register of Historic Places, as well as some state landmarks.

ALABAMA

Birmingham:

Bethel Baptist Church, Parsonage, and Guard House

Bethal Baptist Church was built in 1926 in the African American working class neighborhood of Collegeville. Reverend Shuttlesworth, a well-known

civil rights leader was pastor of Bethel Baptist Church from 1953 to

1961. He participated in several desegregation protests that gave this

church national recognition.

Mobile:

The Campground

The Campground historic district has played an important role in the historical

development of the predominately black community of Mobile, Alabama

since the 1860s.

Montgomery Greyhound Bus Station

On May 20, 1961, the Freedom Riders were attacked by a local mob at this bus station. The repercussions of this one day brought Civil Rights struggles into sharp relief and caught national and international attention.

Selma:

Brown Chapel AME Church

This church served as a starting point for the Selma to Montgomery Marches in 1965, and it played a major role in events that led to the adoption of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Tuskegee:

Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site (Tuskegee University)

This university was part of the expansion of education for blacks in the South following the U.S. Civil War. A historically black college, it first opened in 1881, as Talladega College, with a student body of 30 and one teacher, Booker T. Washington. It features the laboratory of early 20th Century’s most famous African American scientist, George Washington Carver.

Tuscaloosa:

Foster Auditorium, University of Alabama

This is the site where Governor George Wallace in 1963 tried to prevent two black students from entering, resulting in Kennedy calling on the National Guard to allow them entry. This became famous as the “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door Incident.”

ARIZONA

Sierra Vista:

Fort Huachuca

This U.S. military fort was created during the Indian Wars of the 1870s and 1880s to protect settlers and travel routes, and later housed black troops or “Buffalo Soldiers” from 1913-1933.

ARKANSAS

Camden:

Camden Expedition Site

This is the site of a host of different Civil War Battle sites. The Poison Spring Battlefield site has significance for African American history, as it is a site where black Union troops suffered heavy casualties. Also, Jenkins Ferry Battlefield is where the Kansas Colored Regiments of the Civil War fought a battle against the Confederacy.

Fort Smith:

Bass Reeves Statue

This statue is dedicated to Bass Reeves who served as U.S. Deputy Marshal in the Indian Territory from 1875 to 1907 when Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territories were combined to become the State of

Oklahoma.

Little Rock:

Daisy Bates House

Mrs. Daisy Lee Gaston Bates resided at this address during the Central High School desegregation crisis in 1957-1958. The house served as a haven for the nine African American students who desegregated the school and a place to plan the best way to achieve their goals.

Little Rock Central High School

This is where the first major confrontation over the implementation of the Brown v. Board of Education 1954 Supreme Court ruling occurred, in 1957.

CALIFORNIA

Allensworth:

Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park

In August 1908 colonel Allen Allensworth and and four other settlers established this town 30 miles north of Bakersfield with the goal of constructing a thriving community, where blacks could create a better life for themselves outside of segregated U.S. society. It features many restored buildings, including the Colonel’s house, historic schoolhouse, Baptist church, and library.

Los Angeles:

The Bridget “Biddy” Mason Monument

This monument honors one of the first prominent citizens and landowners in Los Angeles during the 1850s and 1860s. Mason, a former enslaved person, founded First African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1872.

Historic Resources Associated with African Americans in Los Angeles, Multiple Property Sumbission

Between the 1890s and 1958, African American settlement patterns in

Los Angeles underwent several distinct phases. Central Avenue was the

hub for much of this period. These national historic sites housed

African American business and community organizations in the area,

including the Lincoln Theater.

Port Chicago:

Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial Park

On July 17, 1944, at Port Chicago, 320 men, mostly African American sailors, were instantly killed when two ships being loaded with ammunition for the Pacific theatre troops blew up. It was World War II’s worst homefront disaster.

COLORADO

Bent County:

Fort Lyon

Founded in 1867, Fort Lyon was in active service to one or more branches of the United States military for 133 years. Several companies of African American (Buffalo) soldiers were stationed here during the Indian Wars from the 1860s to the 1890s.

CONNECTICUT

Farmington:

First Church of Christ

This church was at the center of community life for Amistad captives and their famous 1840-1841 trial.

Austin F. Williams Carriagehouse

This site served as living quarters for the Amistad Africans on their way back to Africa, and as a “station” on the Underground Railroad.

DELAWARE

Newark:

Iron Hill School

This school is one of more than 80 schools for African-American children built between 1919 and 1928 as part of philanthropist Pierre Samuel du Pont’s “Delaware experiment.” Though small and modest, these school buildings incorporated the latest design concepts in Progressive era education.

Wilmington:

Howard High School

This is one of the schools directly associated with the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education. Founded in 1867, Howard High School was the first school in Delaware to offer a complete high school education to black students and was one of the earliest black secondary schools in the Nation.

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

Washington:

Blagden Alley — Naylor’s Court Historic District

After the Civil War, many African Americans migrated to Washington and came to live in the alley dwellings of Blagden Alley and Naylor Court, among others. They were small and poorly constructed buildings, mainly of wood and brick. The living conditions were overcrowded and unsanitary. Only a handful of such alleys still exist. Also located in this historic district isthehome of

slave born Blanche K. Bruce, who was the first African American to serve

a full term in the U.S. Senate, from 1875-1881.

Charles Sumner School

Named after U.S. Senator Charles Sumner, a major figure in the fight for abolition of slavery and the establishment of equal rights for African Americans, it was one of the first public school buildings erected for the education of Washington’s black community. Since its dedication in 1872, the School’s history encompasses the growing educational opportunities available for the District of Columbia’s African Americans.

Frederick Douglass House

This 20-room colonial mansion is where Douglass lived for the last 13 years of his life. It has been preserved as a monument to the 19th century abolitionist.

Greater U Street Historic District

This historic district is significant as the center of Washington’s African American community between c.1900 and 1948, with African American owned and operated businesses, entertainment facilities, and fraternal and religious institutions.

John Philip Sousa Junior High School

This school stands as a symbol of the lengthy conflict that ultimately led to the racial desegregation of public schools by the Federal government in Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Lincoln Park

This Park features the Mary McLeod Bethune memorial and the Abraham Lincoln Memorial. The

statue of Lincoln is at the East end of the park, whereas Bethune’s

statue lies to the West. Unveiled in 1974, this is the first monument to

a black person, or even a woman.

Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial

This solid granite sculpture of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., stands in the “National Mall” in Washington, D.C. The monument, opened in August 2011, commorates King’s fight for civil rights and the year that the 1964 Civil Rights Act became law.

Mary Church Terrell House

This house, built between 1873 and 1877, was the home of Memphis-born Mary Church Terrell, who at age 86 led the successful fight to integrate eating places in the District of Columbia.

Mary McLeod Bethune’s Council House

This townhouse is where Bethune achieved her greatest recognition. It was the first headquarters of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) and was Bethune’s last home in D.C. From here, she brainstormed programs and strategies to advance the interests of African American women.

Metropolitan AME Church

This is the oldest African Methodist Episcopal church in D.C., having been built in 1838. Throughout its history, the church has had parishioners who were very important in the history of Washington’s African American community, including Frederick Douglass and Altheia Turner. Funeral services for Frederick Douglass and former US Senator Blanche K. Bruce were held at the church.

Mount Zion Cemetary

This cemetery serves as a physical reminder of African American life and the evolving free black culture in the District of Columbia from the earliest days of the city to the present.

Ralph Bunche House

This house is where Dr. Ralph Bunche, the distinguished African American diplomat and scholar, from 1941 to 1947. Bunche served as a full professor at Howard University and as Undersecretary-General of the United Nations at this time. He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1949.

Andrew Rankin Memorial Chapel, FrederickDouglass Memorial Hall, and Founders Library, Howard University

From 1929, Howard Law School became an educational training ground,

through the vision of Charles Hamilton Houston, for the development of

activist black lawyers dedicated to securing the Civil Rights of all

people of color. Howard University is nationally significant as the

setting for the legal establishment of

racially desegregated public education.

Public Schools of Washington D.C.

This multiple site historic landmark includes Alexander Crummell School, William Syphax School, and Military Road School, all formerly African American segregated schools.

Striver’s Section Historic District

Since the earliest development of this district in the 1870s, the area has been associated with African American leaders in business, education, politics, religion, art, architecture, science and government. The most renowned of these figures was Frederick Douglass.

FLORIDA

Daytona Beach:

Howard Thurman House

Author, philosopher, theologian, and educator Howard Thurman spent most of his childhood in this late 19th-century house. His influential work influenced Martin Luther King, Jr. and provided the philosophical foundation for a nonviolent civil rights movment.

The Mary McLeod Bethune Home

This was the residence of the educator and civil rights leader on the campus of Bethune Cookman College from the early 1920s until her death in 1955.

Florida Keys:

USS Alligator

Built in the Boston Navy yard in 1820, this warship saw duty in 1821 and 1822, patrolling the west coast of Africa on anti-slavery trade duty. The wreck of the U.S. Schooner Alligator can be found near the Alligator Reef Lighthouse on the Atlantic Ocean side of the Florida Keys, Florida.

Franklin County:

British Fort Gadsden

This fort was once a place where runaway slaves lived alongside Seminole Indians. It was built in 1814 as a base for recruiting Blacks and Indians during the War of 1812. The British abandoned it to their allies in 1815, after which it became a beacon for rebellious slaves.

Jacksonville:

American Beach Historic District

American Beach near Jacksonville, Florida, was founded in 1935 by the Afro-American Life Insurance Company of Jacksonville as an oceanfront resort for African Americans. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2002.

Bethel Baptist Institutional Church

Bethel Baptist Institutional Church is the oldest black Baptist Church in Florida. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

Kingsley Plantation

This is the oldest known plantation in Florida, established in 1763. The plantation has been restored as a house museum. It displays exhibits and furnishings that depict plantation life during the period of 1763-1783.

Palm Beach:

Hurricane of 1928 African American Mass Grave

This is the burial site of approximately 674

victims, primarily African American agricultural workers, who were

killed in the hurricane of 1928 that devastated South Florida. It was

one of the worst natural disasters in American history.

St. Augustine:

Fort Mose

Fort Mose is the site of the first free African settlement in what is now the United States. Founded in 1738 by Spanish colonists offering asylum to slaves from the British Colonies, it is also one of the original sites on the southern route of the Underground Railroad.

Lincolnville Historic District

This historically black neighborhood was

originally founded in 1866 by former slaves. Jim Crow laws from 1890 and

1910 spurred the growth of Lincolnville’s black owned and operated

commercial enterprises, and in 1964 its politicized community

institutions became the sites and bases from which many Civil Rights

Movment marches began.

GEORGIA

Atlanta:

Atlanta University Center Historic District

Created in 1929, this consortium of historically black colleges includes the Clark Atlanta University, Spelman College, Morehouse College and the Morehouse School of Medicine. Students are able to cross-register at the other institutions in order to attain a broader collegiate experience. Several ot these institutions played an important role in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Martin Luther King Historic District

This National Historic Site located within several

blocks of Atlanta’s Auburn Avenue features King’s birthplace home,

gravesite, and the church where King served as assistant pastor.

Sweet Auburn Historic District

This historic African American neighborhood is where African American businesses moved after the Atlanta Race Riot of 1906.

Albany:

Mount Zion Baptist Church

Constructed in 1906, this brick church served as the religious, educational, and social center of Albany’s African American community, especially during the Civil Rights Movement.

Augusta:

Paine College Historic District

Representing one of the few institutions of higher education created by a biracial board of trustees in Georgia for African American students in 1882, Paine College Historic District is important for its role in education and African American heritage.

Midway:

Dorchester Academy Boys’ Dormitory

Dorchester Academy was founded by the American Missionary Association (AMA) following the Civil War as a primary school for black children in the 1890s. It is is nationally important as the primary site of the Citizenship Education Program sponsored by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) between 1961 and 1970.

Sapelo Island:

Behavior Cemetery

This cemetery is a unique post civil-war African American burial ground that reflects African American burial customs. The oldest tombstone death date is 1890, although tradition holds that burials have taken place at this location since antebellum times.

Vienna:

Vienna High and Industrial School

Built in 1959, Vienna High and Industrial school is as an excellent example of an equalization (an educational facility created to be equal among African-American and white students) school in Georgia and is significant in the areas of architecture, education, ethnic heritage and social history.

ILLINOIS

Chicago:

Chicago Bee Building

This is the home of the Chicago Bee, an African American newspaper commissioned to this building by black entrepeneur Anthony Overton in 1926.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett House

This was the former home of late 19th Century and early 20th Century civil rights advocate Ida B. Wells.

Robert S. Abbott House

Abbott lived in this house from 1926 to 1940. He founded the black newspaper, TheChicago Defender. Under Abbott, TheChicago Defender

encouraged blacks to migrate north. It was responsible for the large

northward migration of blacks during the first half of the 20th century.

Oscar Stanton DePriest House

This house was the residence of the first black American elected to the House of Representatives from a northern state.

Overton Hygienic Building

This is one site that has given the African American community in Chicago the name “Black Metropolis.” Established in the beginning of the 20th century by Anthony Overton, this commercial district developed in response to the restrictions and exploitation blacks experienced in the rest of the city, providing venues for African American professional businesses.

Wabash Avenue YMCA

This YMCA was a major social and educational center in the “Black Metropolis,” the center of Chicago’s African American culture in the early 1900s.

INDIANA

Angola:

Fox Lake Resort Community

The Fox Lake resort community was developed specifically for African Americans in the 1930s, when such communities were quite rare.

Richmond:

Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church

Founded in 1836, this site is the oldest African American church in the state.

IOWA

Des Moines:

Burns United Methodist Church

Founded in 1866, this site is the oldest African American church in Iowa.

KANSAS

Fort Leavenworth:

Buffalo Soldiers Memorial Park

This park, on the grounds of historic Fort Leavenworth, is dedicated to the Buffalo Soldiers who served in garrisons throughout the West from 1866 through World War I.

Kansas City:

Quindaro Ruins

This town became an important station on the

Underground Railroad, with slave escpaing from Platte County and hiding

with local farmers before traveling to Nebraska for freedom. The town

was abandoned by most of the inhabitants with the outbreak of the Civil

War.

Nicodemus:

Nicodemus Historic District

This site is where a predominately black community was established in 1877 in western Kansas, during the reconstruction period after the Civil War. It is a symbol of the pioneering spirit of formerly enslaved people.

Topeka:

Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site

This is the site of two Topeka schools: Monroe Elementary School and Sumner Elementary School. Both played a significant role in the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education.

KENTUCKY

Berea:

Lincoln Hall, Berea College

Founded in 1887 to educated both black and white students, this hall on the Berea College Campus served as the focus of civil rights activity for nearly a century.

Nicholasville:

Camp Nelson

Camp Nelson was a large Union quartermaster and commissary depot, recruitment and training center, and hospital facility established during the Civil War in June 1863. After March 1864, Camp Nelson became Kentucky’s largest recruitment and training center for black troops.

Simpsonville:

Whitney M. Young, Jr. Birthplace

Educator and civil rights Leader Whitney M. Young lived at this home until he was 15. He spent most of his career working to end employment discrimination in the South and turning the National Urban League into a strong grass roots organization for racial justice.

LOUISIANA

Alexandria:

Arna Wendell Bontemps House

This house is the birthplace of writer Arna Bontemps, a major figure in the African American literary movement known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Dorseyville:

St. John Baptist Church

Built between 1871 and 1875, the church is significant because it represents the earliest period of the African-American community in Dorseyville, which formed this town, located in sugar cane plantation fields, just after the Civil War.

Jackson:

Port Hudson

This was the site of a 48-day long Civil War siege, when 7,500 Confederates resisted some 40,000 Union soldiers for almost two months in 1863. Union casualties included 600 African-Americans of the First and Third Louisiana Native Guards.

New Orleans:

James H. Dillard Home

This is the former residence of Dillard, who spent most of his life improving the education of blacks in the U.S.

Eagle Saloon, Karnofsky Tailor Shop and House, and Iroquois Theater

In the first half of the twentieth century, South Rampart Street was once a flourishing entertainment and commercial district for African Americans containing drugstores, barber shops, theaters, live music venues, combination grocery stores/saloons, second-hand stores, saloons and pawn shops, of which these sites are an example.

Oscar:

Cherie Quarters Cabins

These twin cabins are all that remain of the slave quarters on the historic Riverlake Plantation. They are a rare surviving example of a once common building type in the antebellum south.

Springfield:

Carter Plantation

In 1817, Thomas Freeman became the first African-American man to own property in Livingston Parish when he acquired the pine forest in this area that he would transform into what has come to be known as the Carter Plantation.

Xavier:

Xavier University Main Building, Convent, and Library

Founded in 1915, this University provided a quality education to thousands of African Americans, principally from New Orleans and elsewhere in Louisiana, despite the widespread inequities during the Jim Crow era.

Wallace:

Evergreen Plantation

This Plantation home is a prime example of the major slave plantations found in the Antebellum period. It is composed of 39 buildings, including a main house and slave quarters. Parts of the movie Django Unchained were filmed at this plantation.

MAINE

Brunswick:

Harriet Beecher Stowe House

It was here that the author Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin between 1850 and 1852.

Portland:

Abyssinian Meeting House

This building was constructed between 1828 and 1831 to serve Portland, Maine’s African American community. Remodeled by the Congregation in the decade after the Civil War, it was used for religious, social, educational, and cultural events until its closing in 1916.

MARYLAND

Cambridge:

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument

President Obama proclaimed this site a national monument in 2013. Its landscape is deeply associated with Tubman and the underground railroad, and is representative of the region in the early and mid 19th centuries. It includes the Jacobs Jackson Home Site, one of the first safe houses along the underground Railroad, Bezel Church, where African Americans worshipped at this time, Stewart’s Canal, which provided an escape route for slaves, and the James Cook Home Site, where Tubman was hired out as a child.

Harford County:

The Hosanna School

In 1867, the Freedmen’s Bureau established the Hosanna School, as known as the Berley School, to provide aid and education to former enslaved blacks and poor whites in the area.

Prince George’s County:

African American Historic Resources of Prince George’s County

Thomas Calloway House was the home of black lawyer and businessman Thomas Calloway in 1908, Ridgley Methodist Episcopal Church

in Landover was built in 1921 and was the spiritual and social center

of the formerly rural African American farming community of Ridgley.

Abraham Hall

was constructed in 1889 in Rossville for the Benevolent Sons and

Daughters of Abraham, a society established for the social welfare of African Americans. In Upper Marlboro, black Roman Catholics founded St. Mary’s

Beneficial Society

in 1880 to provide for the social welfare of their community. They constructed a Society Hall in 1892 to serve as a meeting place, social and political center, and house of worship.

MASSACHUSETTS

Boston:

African Meeting House

Around 1800, this site was the first meeting place of the African Baptist Church, the oldest African American church in the state.

Boston African American National Historic Site

In the heart of the Beacon Hill neighborhood, this site interprets fifteen pre-Civil war structures relating to the history of Boston’s 19th century African American community, including the Museum of Afro-American History’s African Meeting House, the oldest African American church in the U.S.

Bunker Hill Monument

This 221 foot statue commemorates the famous Revolutionary War Battle at Bunker Hill, in which a number of blacks fought alongside the colonists.

William C. Nell Residence

Nell was a leading black abolitionist and law student who refused to take an oath to be admitted to the bar because he did not want to support the Constitution of the U.S., which he felt compromised the powers of slaves. He organized meetings in support of the anti-slavery movement.

William Monroe Trotter House

This is where noted black journalist and civil rights activist William Monroe Trotter lived during the first decades of the twentieth century.

Cambridge:

Maria Baldwin House

This house was where Baldwin, the first female African-American principal in a Massachusetts school, lived from 1892 until she died in 1922. She was a leader in many community organizations and a sponsor for many charitable activities.

Great Barrington:

W.E.B. DuBois Boyhood Homesite

This is where prominent black sociologist, writer, and major figure in the black civil rights movement, W.E.B. DuBois, lived during the first half of the twentieth century.

Medford:

Royall House & Slave Quarters

This site is the home of the largest 18th century slaveholding family in Massachusetts. Today, it is a museum that houses archeaological artifacts and household items. The slave quarters are the only slave quarters still standing in the northern United States.

Northampton:

Dorsey-Jones House

Dorsey-Jones House was the home of two escaped slaves, Basil Dorsey (1810-1872) and Thomas H. Jones (1806-1890). Dorsey bought the home in 1849, and it became a haven for those escaping through the assistance of the Underground Railroad.

MICHIGAN

Detroit:

First Congregational Church of Detroit

This church served an important role as the last stop in a long journey for fugitive slaves taking the underground railroad to Canada.

Ossian Sweet House

This home of black physician Ossian Sweet became the site of a racial incident that resulted in a nationally publicized murder trial.

Second Baptist Church

Established in 1836 by 13 former slaves, this was the first African American Congregation in Michigan. Just miles away from the freedom that the Canadian border offered to escaped slaves, the church became a stop on the Underground Railroad.

MINNESOTA

St. Paul:

Pilgrim Baptist Church

Founded in 1863, this is the oldest black church in Minnesota.

MISSISSIPPI

Clarksdale:

WROX Building

From 1946-1954, this building served as the site of a radio station that catered to an African American audience. The second floor, home to WROX, remains unaltered from the time of the radio station’s occupancy.

Natchez:

Natchez National Cemetery

This cemetery is the final resting place of many blacks who fought in the U.S. Civil War. For example, Hiram R. Revels, the first black elected to U.S. Senate, recruited blacks for the Union side during the war.

Tougaloo:

Tougaloo College

Thishistorically black but integrated college was founded in 1869 by the American Missionary Association. During the 1950s and 1960s, it became a primary center of civil rights movement activity in Mississippi.

MISSOURI

Clarkton:

Charles and Betty Birthright House

For more than 40 years this house was home to the Birthrights, former slaves who achieved economic independence and prosperity while building close ties with the families that had held them in slavery, and the predominantly white citizenry of Clarkton and Dunklin Counties.

Diamond:

Carver National Monument

This monument commemorates the place where famous black scientist George Washington Carver was born and spent his childhood. He was discovered by Booker T. Washington in 1896. That same year, Carver joined the faculty of Tuskegee Institute where he conducted the research that made him famous.

Homestown:

Delmo Community Center

This community center was the historic social and political center of Homestown, originally known as South Wardell, one of ten communities constructed by the Farm Security Administration for displaced sharecroppers and tenant farmers following the January 1939 roadside sharecropper demonstration in Southeast Missouri.

Jefferson City:

Lincoln University

This university was launched through the generous philanthropy of former slaves who fought for their freedom during the Civil War. It began as a 22 square foot room in 1866, following the tenets of Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee Institute.

St. Louis:

Old Courthouse (Jefferson National Expansion Memorial)

This is the courthouse where Dred Scott, the most famous fugitive slave of his day, first filed suit to gain his freedom in 1847.

Shelley House

This is the home that the J. D. Shelley family purchased in a fight for the right to live in a home of their choosing. As a result, the United States Supreme Court addressed the issue of restrictive racial covenants in housing in the landmark 1948 case of Shelley v. Kraemer.

MONTANA

Great Falls:

Union Bethel AME Church

The Union Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) in Great Falls, Montana, is one of the first-built and longest-used churches for African Americans in Montana.

NEBRASKA

Omaha:

Malcolm X House Site

Civil Rights activist Malcolm X was born in a now demolished house on this site.

NEVADA

Las Vegas:

Berkely Square

The Berkely Square subdivision, which is located in the area historically known as Las

Vegas’ Westside, consists of 148 Contemporary Ranch-style homes designed

by internationally-known African American architect Paul R. Williams.

It was built between 1954 and 1955 and was the first minority (African

American) built subdivision in Nevada.

Moulin Rouge Hotel

This was the first interracial hotel built in Las Vegas, constructed in 1955, at a time when black performers and visitors were denied access to casino and hotel dining areas and were forced to seek accomodation in black boarding houses. Despite community aims to preserve the site, all that remain of the structure are two pillars in an empty lot.

Reno:

Bethel AME Church

This church was a religious, social and political center of the African American community, initially for black settlers in Reno Nevada in the 1910s, and later for local civil rights activists during the 1960s.

NEW HAMPSHIRE

Lee:

Cartland House

This building is where Moses Cartland, one of New Hampshire’s premier antislavery activists, aided those fleeing from slavery in the mid-19th century.

NEW JERSEY

Newark:

Newark Symphony Hall

Built in 1925, the Newark Symphony Hall saw its first African American performer, Marian Anderson, in 1940. Since then the hall has been a major venue for African American musical and performing artists. It continues to serve as a cultural center for the Greater Newark-New York City Region.

Paterson:

Hinchliffe Stadium

This stadium served as the home field for the New York Black Yankees between 1933 and 1937, and then again from 1939 to 1945. Hinchliffe is possibly the sole surviving regular home field for a Negro League baseball team in the Mid-Atlantic region.

Red Bank:

T. Thomas Fortune House

This National Historic Landmark was where former slave and leading black activist and journalist T. Thomas Fortune lived from 1901-1915.

NEW MEXICO

Albuquerque:

Philips Chapel Church, Las Cruces

This century-old church is the oldest African American religious institution in Southern New Mexico.

NEW YORK

Auburn:

Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged, Harriet Tubman Residence, and Thompson AME Zion Church

These properties illustrate Harriet Tubman’s life in Auburn, New York, between 1859 and 1913. Her Home for the Aged is a charitable organization for aged and indigent African Americans which she founded; her residence; and, the Thompson AME Zion Church on Parker Street, where she worshipped.

Buffalo:

The Reverend J. Edward Nash, Sr. House

J. Edward Nash, Sr., the son of freed slaves, came to Buffalo from Virginia in 1892 to

serve as the pastor of the Michigan Street Baptist Church, an

appointment he held until 1953. Nash was well acquainted with African

American leaders on the national stage in his day, particularly Booker

T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, and Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, Sr. He

was instrumental in establishing branches of the National Urban League

and the NAACP in Buffalo.

Newburgh:

Newburgh Colored Burial Ground

The Newburgh Colored Burial Ground is a historic cemetery located on