_edited.jpg)

.png)

HEROES MUSEUM (PAGE 2)

We would love to take the time to honor our Heroes "That Walked Among Us". Remembering all of our heroes and giving them the full credit they deserve. Enjoy your time at our museum and let us know in the Virtual Village your thoughts. Thank You!

*NOTE*

UNMUTE the video to hear the audio. Thank You!

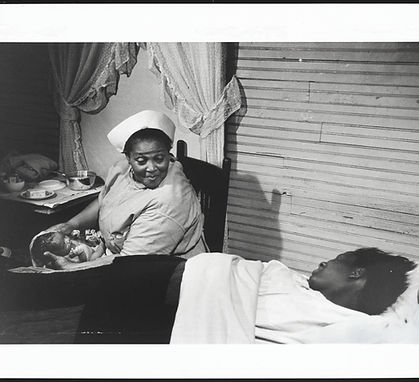

The ‘Black Angels’ Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis

The exodus of white nurses began in spring 1929, months before the stock market crash. Without warning, they hung up their uniforms and walked out of Sea View Hospital, New York’s largest municipal sanatorium. Their reasons for leaving varied. Some blamed the 14-hour shifts and five-hour round-trip commute from Manhattan to Staten Island, where the hospital was located. Others blamed the emotional and mental toll the job demanded, caring for the city’s indigent consumptives who lay in its wards, dying of tuberculosis.

Nicknamed the “Pest House,” Sea View sat on an isolated hilltop 400 feet above sea level, overlooking New York’s lower bay where it spills into the North Atlantic. Sprawling across 300 acres, the complex boasted dozens of buildings, including two chapels, a synagogue, a morgue, a theater, a nurse’s residence and eight austere five-story pavilions that seemed to rear against the sky. Inside, almost a thousand patients lay in open wards, languishing as millions of microbes gnawed at their tissues, organs and bones. All day, patients struggled to breathe, as long-lasting coughing fits often cracked their ribs, causing them to choke and gag and send swarms of live germs into the air. The bacteria settled onto bedpans, nightstands, bed frames and nurse’s carts. It floated under beds and down hallways, sneaking into every corner of the ward.

For years, the white nurses had watched their colleagues grow ill. They saw their faces turn ashen and their eyes glisten from a fever that sent the mercury soaring, causing drenching sweats and wild hallucinations. Some recovered, but others died in the wards where they once worked. Wanting to avoid the same fate and knowing they had plenty of options for jobs that wouldn’t kill them — stenographers, secretaries, librarians, salesclerks — the nurses began quitting, abandoning Sea View, their patients and the disease that had dogged New York City for decades.

The Plague of New York City

Beginning in the early 1900s, tuberculosis spread throughout the city, finding willing hosts in the waves of European immigrants who arrived daily. Stepping off the ships with their suitcases and bundles, many headed to Manhattan’s Lower East Side, where nearly 80,000 five-story tenement buildings collectively housed 2.3 million people, almost two-thirds of New York’s population. Sometimes, entire generations lived inside these buildings, which were described as “fever breeding structures” by photojournalist Jacob Riis. The families lived and worked in 300-square-foot apartments with scant fresh air and sunlight.

City officials like Dr. Hermann Biggs, the general medical officer for New York City, despised these buildings and the people who lived in them. For years, Biggs tried to control the spread of tuberculosis through a series of public health measures: disease maps, registration laws, tent colonies, mass mailings, posters and even a “health clown” who sang health ditties to children living in the slums. But nothing stopped the disease from spreading.

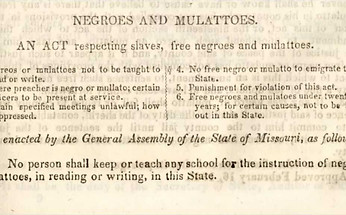

In the 1920s, Black nurses could only work in Black hospitals. America had approximately

260 Black hospitals compared to over 6,000 white ones.

Biggs grew desperate and turned to city officials, imploring them to build a hospital as a “necessary protection for those who don’t have TB but are exposed to it by the carelessness of others.” The city obliged and opened Sea View in 1913; within days, it reached its capacity of 800 patients. By 1920, the hospital had helped lower New York’s annual death rate from 10,000 to a little more than 5,000. But there it stalled, turning Sea View’s triumph into the city’s nightmare.

Tuberculosis was the third leading killer in New York and the fourth globally. If officials couldn’t restaff the wards, they would be forced to close them, releasing hundreds of highly contagious patients into the city. Infection rates would rise, and decades of progress would be reversed. New nurses had to be found — immediately.

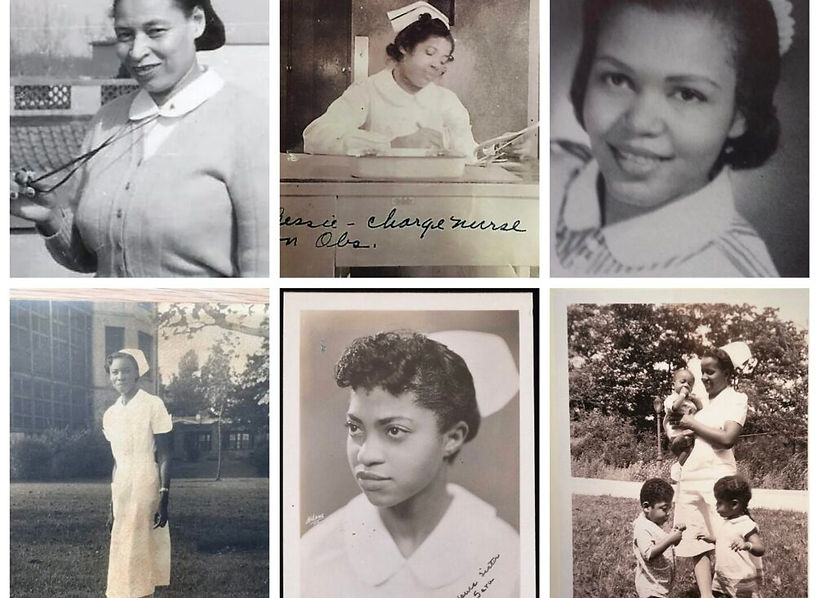

Top row: Jane Shirley; Bessie, a charge nurse; Curlene Jennings. Bottom row: Phyllis Alfreda Hall, Salaria Kea, Virginia Lee Greene. (Credit: The Shirley family, Greene family, the Bennett family, the Allen family, and the Sea View archives, via The Emancipator)

Health officials and infectious disease experts scrambled to replace the white nurses, holding emergency meetings. Soon, an idea emerged. Labor recruiters had successfully enticed Black sharecroppers and farmers to come north and work in their slaughterhouses, steel mills, kitchens and factories. Despite the intensity of the labor, for many, it was a small price to pay for a steady, well-paying job and freedom from the constraints of Jim Crow. “I make $75 per month. I … don’t have to mister every little white boy that comes along,” wrote one migrant in a letter. Given the success in luring laborers and domestics, there was no reason a similar tactic wouldn’t work for professional Black women in nursing.

Across the South, hundreds of trained Black nurses remained unemployed because the same country that drew lines around water fountains, bus stations and waiting rooms also drew them around hospitals. At the time, Black nurses could only work in Black hospitals, and in the 1920s, America had approximately 260 Black hospitals compared to over 6,000 white ones. If a white hospital did hire Black nurses, the white supervisors often delighted in verbally and emotionally abusing them. In Alabama, the director of public health believed that Black nurses had “limited intellectual capacity,” making them “incapable of abstract thinking.” In Atlanta, the superintendent for Grady Hospital declared they had “no morals, and unless they are constantly watched, they will steal anything in sight.”

To lure the nurses north, the city would offer them a package deal: free schooling at Harlem Hospital School of Nursing, on‑the-job training, housing, a salary and, above all as they saw it, a “rare opportunity” to work at one of the city’s integrated municipal hospitals. Only four of New York’s 29 hospitals employed Black nurses at the time.

During the 1930s and 1940s, hundreds of nurses answered the call. Eager to live free from the daily constraints of segregation — the back doors, the “yes, sirs,” the colored fountains, the waiting areas — they packed up their lives and left southern cities and rural towns. Alongside the laborers, these often-overlooked professional women boarded Jim Crow trains and buses, their nurses’ whites tucked into suitcases atop Bibles and photographs, and settled in for the long trip north.

On one of those trains sat Missouria Louvinia Walker-Meadows, fresh from Howard University and determined to put down new roots and fight against inequality. Kate Gillespie also came, fleeing Alabama with her young son to spare him, her family said, “from seeing the strange fruit growing on trees,” as did nurses Nellie Mae Holmes and Leola Washington.

Then there was 28-year-old Edna Sutton from Savannah, Georgia. Born in 1900 on the floor of a tar-paper shack in one of Savannah’s shantytowns, Sutton dreamed of becoming a surgeon, an aspiration many believed was impossible for a Black woman. But her father, an enslaved man, had inspired his daughter after he walked off his plantation in Wilkes County, Georgia, in 1899 to arrive in Savannah, where he reinvented himself and became a preacher. He had taught her to dream big; so after high school, she enrolled in one of Savannah’s two Black training schools for nurses.

The Long Road to a “Wonder Drug”

The nurses also dealt with racism inside the institution, personified by their supervisor, Lorna Doone Mitchell, a Teutonic white woman and the daughter of a Confederate medic, who wielded her power in perverse ways. She lurked in hallways, hoping to catch the nurses doing something wrong, refused requests for transfers and prevented them from wearing masks on a regular basis. Masks, she said, made them “complacent.” Then there was the president of hospitals, a man who held the racist vision that Black nurses were expendable. At a meeting in 1933, he was asked why the city sent Black nurses to Sea View. “Because in 20 years,” he said, “we won’t have a colored problem in America because they’ll all be dead from TB.”

However, they didn’t die. Instead, the nurses relied on their professional status and know-how to band together, organize and fight for equality by creating petitions and policies that helped to desegregate the New York City hospital system. On a national level, they joined nurse leaders Estelle Massey Osborne and Mabel Keaton Staupers to advocate for integrating Black nurses into the American Nurses Association. They brought that same spirit home to Staten Island, fighting redlining by hiring lawyers and enlisting the NAACP to help them buy the homes they wanted on the streets they desired. They proceeded to build a middle-class community and represent Black America as career-driven homeowners.

But mostly, the Black nurses of Sea View uplifted the industry they were called to serve by broadening human rights and caring for a patient population who, like them, was seen as disposable. In doing so, they became experts at their jobs. In 1951, Dr. Edward Robitzek trusted Sea View’s nurses to oversee the first human trials of isoniazid to see if it could prevent the spread of tuberculosis bacteria, referred to by one journalist as “the most grandiose experiment ever undertaken in the history of medicine.” Their work on those trials led to the Feb. 20, 1952 announcement, where the New York Post prematurely broke the news about a cure with the banner headline, “Wonder Drug Fights TB.” In a single galvanizing moment, the course of history was altered. It was triumphant, and as Robitzek later said, “none of it would have been possible without the nurses.”

In a photograph taken that day, the once-incurable TB patients jitterbugged front and center. In the back stand the Black nurses, their faces staid and somber. Their experience tells a more complex story, one of the women who saw terrible things; who did the impossible by prevailing over one of humanity’s greatest scourges; who followed orders from physicians who themselves were at a loss; who worked through trial and error, sometimes prescribing unreliable medications that often made people sicker; who stood in surgical rooms watching operations turned to butchery.

They did it because it was their job; because they were professionals who had committed themselves to saving lives at the risk of their own. But, also, because they were Black women, subjects of Jim Crow labor laws that offered them two options: stay in the South and dream of becoming a professional, or rise and join the Great Migration and actually become one. These women, whom patients came to call the Black Angels, chose the latter.

No one can deny that after Covid-19, the next public health crisis will come. Once again, the most vulnerable, ambitious, and aspirational among us will be called and tasked with working tirelessly to keep Americans safe and their patchwork of a health care system from completely coming undone. And if we keep asking nurses like the Black Angels to bear this impossible burden — all while being undervalued and underpaid — then the next crisis just might be our last.

THOSE WHO REFUSED TO GIVE UP THEIR SEAT BEFORE ROSA PARKS

Sarah Keys (1952) - veteran | Claudette Colvin (1955) - 15yr old | Aurelia S. Browser | Mary Louise Smith- 18yr old

The Battle of A' asu' in 1787

While there were many rites and rituals and punishments to avoid, even the ifoga (forgiveness ceremony) was not always accepted when offered; however, if rejected the district claiming to be offended would proceed to publicly humiliate the prisoner and put him to death, in the same manner and with the same indifference as they might slaughter a sacrificial pig. The prisoner was forced to gather the fuel, including wood, rocks and bamboo, for the fire in the umu in which he would be burnt to death promptly.

If the offending side did not accept this harsh result as a final resolution, war would follow, with swift results. Villages and districts were always quick to line up neighboring villages and people to form protective alliances.

War was conducted according to well established routines. The first step in preparation was to protect the women and children by removing them to safety from their hiding places and relocating them to another district or neighboring village. Wives who were especially loyal to their husband or chief were permitted to follow alongside, tending to the wounded, and taking care of those recovering in temporary shelters along the warpath. A brave and loyal woman would always be behind her husband wherever he went, holding his war clubs and the other weapons and provisions he might need.

Many chiefs took bundles of fine mats to different villages and districts to encourage or entice the leadership there to join them in an alliance. Good relationships after the war were prized, since when hostilities ended, some soldiers might not return to their districts to resume family and village life. Loyalty was prized above all. When warriors were selected, all boys who were able to hold a weapon, even if only a stick, were included. Refusal to go to war with one’s village means his title would be stripped and he would be banished from the village forever.

There were districts and villages which used the highest and most honorific title ‘aumua. These warriors would lead the village soldiers into battle, going first, giving and taking the greatest violence and bloodshed. For this reason, twice as many of them died in wars than those who came later. In spite of their high casualties, they were intensely proud of their position as leaders in war, a distinction they would not readily give up. Their strength and bravery were praised and they became famous. When war subsided and some peace prevailed over the land, villagers would show their respect by giving them a proper meal to reward their bravery.

The line of command was strict and unwavering. During a war, the High Chiefs and Talking Chiefs made all the decisions; the decisions of the High Chiefs were invariably supported by the Talking Chiefs.

Weapons included war clubs, spears and slings. In time, metal became available, and the weapons they made included those with potential to inflict extreme damage to the enemy: these included the to’ifaufau (an axe or an adze) or a to’imulifao (an axe like a hammer) with handles as long as a walking stick. Later on, as the international community appears, they were able to procure arms from overseas, including the pelu (machete) , the fanagutuolo (the revolver) and other guns such as the fanamanu, and a spear to put in the mouth of the fana pulusila.

Strategy and tactics were quite predictable. The warriors would encircle a village where the enemy was encamped and build towers out of trees about 8 feet high, covering the spaces in between with the camouflage of other trees. Once ready, they waited about an hour before striking the unsuspecting enemy. It was rarely more than a mile or two between the towers and settlements, so in caution, they approached the enemy going to the far side of the encampment to encircle and outflank them. Fighting in the woods made identification difficult, so they created symbols to recognize one another using secret code, often drawing these on their cheeks with charcoal, or writing lines next to the symbol, which might be a dog or a bird or even a tree branch. Sometimes they would tie a piece of tapa around their neck, perhaps with fish tied to it.

Likewise they marked their boats with symbols to make recognition easier,

raising flags on their masts with the painted symbols on them.

The intention to go to war was never made secret. Instead, it was customary before all planned wars to set aside a day for entertainment and dancing to recognize and honor the warriors. But once the war began, they did not attack immediately. They preferred stealth. The aim was to surprise and seize the unsuspecting enemy when they were unprepared. In many wars, no more than 50 warriors might die from each side. All male prisoners were executed, and all the captured women were distributed among the stronger warriors of the winning side.

The brave warriors were usually very fast, like ‘asaeli (meaning “One with the Lord of the Lords” and most likely originating from the term “Israel”) in the Holy Bible. These warriors would jump in front of a gathering and throw their spears; they rarely missed. They were also able to stand firmly in place for hours with their war clubs protecting themselves by batting down the spears being thrown at them.

The wars were very bloodthirsty; the warriors took extreme pride in their skills, demonstrating their prowess by the number of heads they had cut off and thrown down in front of their chiefs and supporters. This demonstrative behavior, and frank glee in killing, was entirely unlike the European soldiers who, in contrast, more resembled those at a sporting event. The happiness and dignity of a Samoan warriors was expressed by this ritual enthusiasm for the number of heads he had taken. The public demonstration was most important. Villagers received the display with a sense of worship, dancing and laughing and they called out his name, the village name, and even the name of the victim, if they knew it. The heads were laid at the feet of his chief, who congratulated him and publicly showed respect and pride. The warrior in turn encircled the others, stomping his feet in a brief dance before leaving to resume his place in battle to bring even more heads from the fallen enemy.

When the battle was over, they would pile the heads in the open field (malae) of the village. Respectfully, the head of the chief, if taken, would be placed at the top of the pile. The families of the victims came to retrieve the remains, and those unclaimed would be buried together in a common pit.

While the heads of the victims were displayed, their bodies were left in the forest, and buried only when known. If unknown, they would be left for foraging wildlife to consume. On occasion, the dead bodies were circulated around the malae and showed extreme inhumanity. In a once recorded story, a missionary became overwhelmed as he watched in horror as a warrior ran into the malae with the chin of his victim between his teeth while dragging the cut up body behind in the dust.

Wars in Samoa always began with an elaborate ceremony; these were often different. They first asked the Gods for victory with a sacrificial offering; they might plant special plants and trees, or bury water wells under camouflage. The planning was elaborate and sophisticated. For a large war with many districts and villages, they would divide the warriors into three separate units, one for the road, one for the forest, and one for the ocean. Typically, thirty to forty canoes prepared to take three hundred or even four hundred warriors. Battles in the forest were equally dangerous as those on the open water, because they did not know where the enemy was hiding or lying in wait, and did not know the hour of attack. That would be revealed only moments before. Secret instructions were key to their success. They would gather, perhaps, in the middle of the night, encircle the village to be attacked, approaching it from the rear, before the village awakened, trapping it between two flanks. After this attack, they would retreat to their canoes waiting in the ocean to carry them off. This was all done hastily, since once alerted, the single young men of the village would be in pursuit of them. If the ambush was discovered promptly, many would be killed and much blood would be shed.

The palagi historians and missionaries record some vivid scenes and memories. In once instance, the gratuitous murder of an old man, found praying innocently, occurs when another thirteen are beheaded; in another a mother wraps herself around a child as is slashed from head to toe, a rare event since killing women was looked upon with great disfavor. She and the child both survived, since they did not find the child who was hiding safely in her arms.

The wide reputation for extreme inhumanity and brutality of the Samoan warriors is not necessarily unfounded. This reputation reached its highest point when the first papalagi encountered Samoans at Tutuila. In 1787 a French expedition, led by Jean Francois de Galaup la Perouse, approached Tutuila and entered the harbor at the village of A’asu. The officer, Paul Antoine Fleuriot de Langle landed on the beach and was greeted by the villagers. He returned to his ship with assurance that it would be safe to go ashore, which they did the next day. A scuffle broke out, and mutual suspicions arose. A rumor began among the palagi that a Samoan man had stolen something from the ship, so he was summarily shot and killed, whereupon his family and the villagers sought revenge. They expressed their anger by throwing rocks, killing everyone on board. Ever since that incident, the people in that village were labeled as wild and ferocious and Europeans were advised by one another never to visit there.

Despite that the Samoans buried all of the palagi who they had slaughtered, unsurprisingly their reputation for ferocity did not abate, and they became known in Europe and elsewhere as “heathens”, although the Samoans were firmly following their own principles of a “just war, “exactly as most other cultures everywhere do.

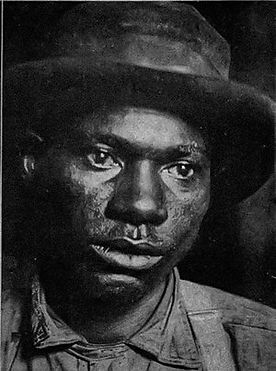

The Red Summer 1920

On September 27, 1919, a mob of at least 10,000 white people stormed the courthouse in Omaha, Nebraska, demanding the sheriff turn over Will Brown, a 40-year-old Black man. They raided the building, scaled walls and smashed windows. When the mob’s initial demands were refused, they set fire to the courthouse, turning it into a seething furnace. Omaha Mayor Ed Smith tried to intervene, but the mob tried to lynch him. Smith escaped badly injured.

From inside the courthouse, terrified white inmates threw down a note surrendering to the mob: “THE JUDGE SAYS HE WILL GIVE UP NEGRO. BROWN. HE IS IN THE DUNGEON. THERE ARE TEN WHITE PRISONERS ON THE ROOF. SAVE THEM.”

The frenzied horde finally broke into the jail and dragged Brown out. They tortured him, dismembered him, tied a rope around his neck and hoisted him up on a pole on the south side of the courthouse. As his body dangled in agony, they shot him more than 100 times. After they were sure he was dead, they sliced the rope and Brown’s body dropped to the pavement. Then the frenzied mob, which the local newspaper referred to as a “lynching committee,” cursed, kicked and spat on the body of the Black man.

Still, the mob of thousands of white men and women was not finished with the lynching. Someone found a new three-quarters-inch rope and tied Brown’s body to a car. Then they dragged his corpse slowly through the crowd, over glass and stones, through the streets to the edge of Omaha’s Black neighborhood, as a symbol of their rage. There, the “lynching committee” poured kerosene on Will Brown.

And lit his body with fire.

As they witnessed burning flesh, hundreds of the well-dressed men stood back and grinned.

They watched the contorted body of Brown, a 40-year-old innocent meatpacker, burn.

A newspaper photographer snapped a photo of the petrified corpse, capturing one of the most horrific photos of racial lynching in U.S. history.

That night, the horde “also murdered at least one other African American who was walking on the streets and caught by the throng,” according to North Omaha History. The rioters “wounded at least 20 policemen; and demolished at least 10 homes in the Near North Side neighborhood.”

That year, Omaha would become one of at least 26 cities across the country where barbaric white mobs attacked Black people and Black communities during a reign of racial terror that author James Weldon Johnson labeled “Red Summer.”

The massacres and lynchings that occurred during “Red Summer,” a term used to describe the blood that flowed in the streets of America, were sparked by disparate events, but the common denominator was racial hatred against a people who had recently risen out of enslavement and prospered.

In Omaha, Will Brown was falsely accused of assaulting a white woman as she walked with her boyfriend. In East St. Louis, it was Black men working factory jobs that white people wanted for themselves. In Longview, Texas, it was a Black man writing a newspaper story about a love affair between a Black man and a white woman. In Washington, D.C., it was an accusation that Black men tried to take a white woman’s umbrella. In Chicago, it was a Black teenager swimming in Lake Michigan and accidently floating over an invisible color line. In Elaine, Arkansas, it was Black sharecroppers trying to get better payment for their cotton crops. In Tulsa, Oklahoma, it was a Black teenager allegedly bumping into a white woman on an elevator.

During “Red Summer,” thousands of Black people were fatally shot, lynched and burned alive. Hundreds of Black-owned businesses and homes in Black communities were obliterated in fires fueled by racism and hatred. Millions of dollars of Black businesses and generational wealth were stolen.

Some historians claim that the racial terror connected with “Red Summer” began as early as 1917 during the bloody massacre that occurred in East St. Louis, Illinois, a barbaric pogrom that would eventually set the stage for the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, one of the worst episodes of post-Civil War racial violence ever committed against Black Americans. The Tulsa Massacre left as many as 300 Black people dead and destroyed more than 35 square blocks of Greenwood, an all-Black community so wealthy, the philosopher Booker T. Washington called it “Negro Wall Street.”

Survivors of the Tulsa Massacre witnessed white men and women descending on Greenwood, killing Black people indiscriminately in what appeared to be ethnic cleansing. Occupied houses of Black people were set on fire. When the occupants ran out, members of the white mob shot them. Elderly Black people were shot as they kneeled in prayer. Black women and children were killed in the streets. Black men, with their hands held up in surrender, were shot dead by whites.

Survivors reported that bodies of Black people were thrown into the Arkansas River, loaded on flatbeds of trucks and dumped into mass graves. In October 2019, the City of Tulsa re-opened an investigation into the search for mass graves. A year later, teams of archeologists and forensic anthropologists found a mass grave in the city-owned cemetery, which could be connected to the massacre. This spring, the City of Tulsa plans to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the massacre, as descendants of survivors demand reparations for what was lost, and protest against current oppression and racism.

results of Red Summer

Nearly a century after the Tulsa Race Massacre, the country would again see another white mob attack. On January 6, 2021, pro-Trump supporters stormed the U.S. Capitol. People watched in shock as insurrectionists scaled the Capitol building, encouraged by the 45th president of the United States. The insurgents—including military veterans, police officers and elected officials—broke through police barricades and poured into the Capitol rotunda. They walked through the labyrinth of the Capitol hunting for members of Congress and threatening to kill then-Vice President Mike Pence and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

“It is just the beginning,” said Kevin Seefried, a white man from Wilmington, Delaware, carrying a Confederate flag into the Capitol.

Historians say that in order to understand the country’s racial divide and the attack on the Capitol, one must understand the racial tensions that led to “Red Summer.” “What we are facing within the racial tension that revealed itself in 2020, coupled with the pandemic, is sadly, ironically and tragically the result of what happened 100 years ago during ‘Red Summer,’ when there was a slew of race riots in American cities,” said Christopher Haley, a historian, writer, filmmaker and producer of the movie Unmarked: African American Cemeteries.

“Many of these riots erupted from tensions expressed between Blacks and whites over Black people’s growing economic and social status.”

Haley said there is a correlation between the Jan. 6, 2021 storming of the U.S. Capitol and the events that led to Red Summer. “I think the correlation is that the people rioting were white supremacists, Nazis or anti-Semitic. They carried Confederate flags. That certainly links itself to those persons during Red Summer who hated the progress of African Americans and politicians. It would be stretching it to say there is no correlation.”

The Chicago Race Riot of 1919

The racial violence in Chicago began on Sunday, July 27, 1919, one of the hottest days in that city’s history. Eugene Williams, a Black teenager, walked to South Side Beach. Eugene, who was 17 at the time, put his make-shift raft into Lake Michigan and began floating in the cool waters.

As he waded, Eugene’s raft mistakenly crossed an invisible color line drawn in the waters of Lake Michigan. Suddenly, a white man trying to protect that invisible color line, began to throw stones at the Black teenager.

The barrage of stones hit Eugene, knocking him off his raft. Eugene fell, sinking into the cold waters. The Black teenager drowned.

His murder would spark one of the worst episodes of racial violence in the city’s history, setting off seven days of clashes. White people climbed into cars and raced through the Black Belt of the city, shooting at Black people, burning and looting Black people’s homes.

“After seven days of shootings, arson and beatings, the Race Riot resulted in the deaths of 15 whites and 23 blacks with an additional 537 injured (195 white, 342 black),” according to the Chicago History Museum. “Since then, a century of African American activism has challenged the racism and social hypocrisy that allowed those responsible for Eugene Williams’s death to elude justice.”

The NAACP investigator Walter White concluded: “The Chicago riot taught me that there could be as much peril in a Northern city when the mob is loose as in a Southern town such as Estill Springs. I was constantly made aware in white areas, especially the Halsted Street area near the stockyards, that eternal alertness was the price of an uncracked skull. I naively believed that I was well enough known in Negro Chicago, despite my white skin, to wander about at will without danger. This fallacy nearly cost me my life.”

As bad as the riot was in Chicago, White would discover that a more violent massacre would occur only weeks later. It would erupt after Black sharecroppers planning to form a union to fight for better crop wages and escape a system of Southern peonage were killed in the muddy fields of rural Arkansas.

“The bloody summer of 1919 was climaxed by an explosion of violence in Phillips County, Arkansas, growing out of the sharecropping system of the South. The incident was fated to affect materially the legal rights of both Negro and white Americans,” White wrote. “Throughout the nation newspapers published alarming stories of Negroes plotting to massacre whites and take over the government of the state. The vicious conspiracy, so the stories ran, had been nipped in the bud, but it had been necessary to kill a number of ‘black revolutionists’ to restore law and order.”

The massacre in Elaine, Arkansas, began on the night of September 30, 1919, when white men fired on a church in Hoop Spur, Arkansas. Inside the church, Black men, women and children had gathered to discuss forming a union to address the peonage debt spiral created by white landowners, who continued to cheat Black farmers out of profits from growing cotton.

Inside the church, the Progressive Farmers and Household Union met. Black veterans inside the church returned fire, killing a white man.

And again, all hell broke loose. Rumors spread that the Black people were rising up in Hoop Spur. Thousands of white rioters from as far away as Mississippi, Tennessee, Texas and Louisiana descended on the rural Black community in Phillips County, hunting and killing hundreds of Black people.

“The press dispatches of October 1, 1919, heralded the news that another race riot had taken place the night before in Elaine, Ark., and that it was started by negroes who had killed some white officers in an altercation,” Ida B. Wells-Barnett wrote in her book The Arkansas Race Riot.

Some historians believe as many as 800 Black people may have been killed in Elaine.

“Later on, the country was told that the white people of Phillips County had risen against the Negroes who started this riot and had killed many of them,” wrote Wells-Barnett, “and that this orgy of bloodshed was not stopped until United States soldiers from Camp Pike had been sent to the scene of the trouble.”

More than 285 Black people were arrested in Elaine and surrounding areas.

The men were taken to court in Helena, Arkansas, chained and forbidden to meet with an attorney. At least 12 of the Black men arrested were tortured and beaten, according to records. The white jailers soaked rags with formaldehyde and pushed them into their noses. They also used electrical shocks against the Black men’s genitals to try to coerce confessions for starting the massacre. After a six-minute trial, 12 Black men were sentenced to die in the electric chair. Seventy-five Black people were sent to prison on sentences from 5 to 21 years.

The Chicago Defender published a letter by Wells-Barnett appealing to Black people across the country to raise money for the Black men condemned to death row in Arkansas.

One of the Black men in jail wrote to Wells-Barnett, thanking her for her help. “We are innercent [sic] men,” he wrote. “We was not handled with justice at all Phillips county Court. It is prejudice that the white people had agence we Negroes. So I thank God that thro you, our Negroes are looking into this trouble, and thank the city of Chicago for what it did to start things and hope to hear from you all soon.”

Moved by the letter, Wells-Barnett took the train to Arkansas, where she talked with some of the wives of the 12 condemned. Then Wells-Barnett, a fearless anti-lynching crusader and journalist, slipped into the jail and spent the day interviewing the Black men.

“They had been beaten many times and left for dead while there, given electric shocks, suffocated with drugs and suffered every cruelty and torment at the hands of their jailers to make them confess to a conspiracy to kill white people,” Wells wrote. “Besides this a mob from outside tried to lynch them.”

After the NAACP took the case, the fate of the men, who became known as the “Elaine Twelve,” made national news. NAACP attorney Scipio Jones took their case to the U.S. Supreme Court and ultimately won their release off of death row.

The Black Prince was the eldest of Queen Phillipa of Hainaut

*Philippa of Hainault was born on this date in 1310. She was the first African Queen of England.

Philippa was of Moorish ancestry, born in Valenciennes in the County of Hainaut in the Low Countries of northern France. Her parents were William I, Count of Hainaut, and Joan of Valois, Countess of Hainaut, granddaughter of Philip III of France. Philippa was one of eight children and the second of five daughters and became the wife of King Edward III. Her eldest sister Margaret married the German King Louis IV in 1324, and in 1345, she succeeded their brother William II, Count of Hainaut, upon his death in battle.

Philippa married Edward at York Minster on January 24, 1328, eleven months after he acceded to the English throne. Unlike many of her predecessors, Philippa did not alienate the English people by retaining her foreign entourage upon marriage or bringing many foreigners to the English court. As Isabella did not wish to relinquish her status, Philippa's coronation was postponed for two years. She eventually was crowned queen on March 4, 1330, at Westminster Abbey when she was almost six months pregnant, and she gave birth to her first son, Edward, the following June.

In October 1330, King Edward commenced his rule when he staged a coup and ordered the arrest of his mother and Mortimer. Shortly afterward, the latter was executed for treason, and Queen Dowager Isabella was sent to Castle Rising in Norfolk. She spent several years under house arrest, but her privileges and freedom of movement were later restored to her by her son. Of her children, Phillipa outlived nine of them. Three of her children died of the Black Death in 1348. Edward, the Black Prince, was the eldest of her fourteen children, who became a renowned military leader.

A medieval writer, Joshua Barnes, said, "Queen Philippa was a very good and charming person who exceeded most ladies for the sweetness of nature and virtuous disposition." Chronicler Jean Froissart described her as "The most gentle Queen, most liberal, and most courteous that ever was Queen in her days." Philippa accompanied Edward on his expeditions to Scotland and the European continent in his early campaigns of the Hundred Years War. She won acclaim for her gentle nature and compassion. She served as England's regent during her spouse's absence in 1346. Facing a Scottish invasion, she gathered the English army and met the Scots in a successful battle near Neville's Cross: she rallied the English soldiers on a horse before them before the battle, which resulted in an English victory and the Scottish king being taken prisoner. She influenced the king to take an interest in the nation's commercial expansion.

She is best remembered as the kind woman who 1347 persuaded her husband to spare the lives of the Burghers of Calais, whom he had planned to execute as an example to the townspeople following his successful siege of that city. This popularity helped maintain peace in England throughout Edward's long reign. Philippa was a patron of the chronicler Jean Froissart, and she owned several illuminated manuscripts; one is currently housed in the National Library in Paris. William's counties of Zealand and Holland and the seigniory of Frieze were devolved to Margaret after an agreement between Philippa and her sister Margaret. In the name of his wife Philippa, Edward III of England demanded the return of Hainaut and other inheritances given to the Dukes of Bavaria–Straubing in 1364–65; he was unsuccessful.

Philippa died of an illness similar to edema on August 15, 1369, in Windsor Castle. She was given a state funeral on January 9, 1370, and was interred at Westminster Abbey. Her tomb is on the northeast side of the Chapel of Edward the Confessor and the opposite side of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile and great-grandfather Henry III. Sculptor Jean de Liège executed her alabaster effigy. Eight years later, Edward III died and was buried next to her. The Queen's College, Oxford, was founded

1963–1973: High-Dose Radiation Tests on Prisoners’ Testicles to Find Sterility Dose

In 1963, prior to flights into space, scientists were concerned about the effect of space radiation on astronauts’ testicles. They also were concerned about radiated gonads of workers at America’s atomic energy plants. So, they conducted experiments designed to test the effects of massive radiation on prisoners’ testicles without any regard for the consequences for the test human subjects.

In an ugly exercise of rudimentary science that is only now coming to a close, a captive group of human guinea pigs — inmates of Washington and Oregon prisons — were lured into a literal balls-out effort to answer those questions. Enticed with cash and suggestions that participating could help win them parole, and lulled by official assurances that the tests were safe, dozens of prisoners between 1963 and 1973 lined up, stripped down and offered their genitalia to what science called “reproductive radiation tests. . . Dozens of prisoners had their testicles bombarded with radiation in the name of science back in the ’60s and ’70s. (Anderson. Balls of Fire, Mother Jones, 2000)

Until 1973, Dr. C. Alvin Paulsen (University of Washington) who was under a private contract with the AEC, conducted “Reproductive Radiation Tests” on 63 prison inmates at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla. He used X-rays on the testicles of 64 prisoners — later reports indicated the number of prisoners was 131 — to find the dose that would make them sterile (KD Steele. Radiation Experiments Raise Ethical Questions, 1994).

His former mentor, Dr. Carl Heller, simultaneously conducted similar experiments on 67 inmates at the Oregon State Penitentiary sponsored by the Pacific Northwest Research Foundation of Seattle. These experiments were also funded by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

The inmates agreed to participate in the experiments having been lured with cash and the suggestion of parole — $5 a month and $100 when they receive a vasectomy at the end of the trial. Most of the subjects were exposed to over 400 rads of radiation (the equivalent of 2,400 chest x-rays) in 10 minute intervals. The risks of radiation had not been disclosed to the incarcerated subjects. Mother Jones (2000) reported that declassified government documents show that NASA officials and some unnamed astronauts sat in on Heller’s meetings.

The Hidden Horrors Of Ghana’s Cape Coast Slave Castles

Have you ever wondered about the dark history behind Ghana’s Cape Coast?

The Cape Coast Slave Castles hold chilling stories of the transatlantic slave trade. These castles, built by European traders, served as holding sites for enslaved Africans before their forced journey to the Americas. Walking through the dungeons, you can almost feel the despair and hear the echoes of those who suffered. The Cape Coast Castle and Elmina Castle are stark reminders of a painful past. Visiting these sites offers a chance to reflect on history and honor the resilience of those who endured unimaginable hardships.

The Dark History of Cape Coast Castle

Cape Coast Castle, located in Ghana, stands as a grim reminder of the transatlantic slave trade. This fortress, once a bustling hub for trading enslaved Africans, now serves as a historical site where visitors can learn about the atrocities committed within its walls. Here are some of the most haunting places inside Cape Coast Castle.

-

The Male Slave Dungeon

The male slave dungeon is a dark, cramped space where hundreds of men were held captive. With little ventilation and no sanitation, the conditions were horrific. Many perished before even leaving the castle.

2. The Female Slave Dungeon

Similar to the male dungeon, the female slave dungeon held women in equally appalling conditions. Women faced additional horrors, including sexual abuse by the soldiers and traders.

3. The Door of No Return

This infamous door marks the final exit point for enslaved Africans before being loaded onto ships bound for the Americas. Stepping through this door meant leaving behind everything familiar, with little hope of ever returning.

The Role of Elmina Castle

Elmina Castle, another significant site in Ghana, played a crucial role in the slave trade. Built by the Portuguese in 1482, it became one of the first European slave-trading posts in sub-Saharan Africa. Here are some of the key areas within Elmina Castle.

4. The Governor's Quarters

The governor's quarters, located at the top of the castle, offered a stark contrast to the dungeons below. Lavishly furnished, these rooms were where the governor lived and conducted business, often overlooking the suffering of those imprisoned below.

5. The Condemned Cell

This tiny, airless cell was reserved for those who resisted or tried to escape. Prisoners placed here faced certain death, either from starvation or suffocation.

6. The Chapel

Ironically, a chapel was built within the castle, where European traders would pray. The juxtaposition of worship and the inhumane treatment of enslaved Africans highlights the moral contradictions of the time.

The Impact on Modern Ghana

The legacy of these castles extends beyond their walls, affecting modern Ghanaian society. Understanding these sites helps in comprehending the broader impact of the slave trade on the region

7. The Memorial Wall

Located near Cape Coast Castle, the memorial wall honors those who suffered and perished during the slave trade. It serves as a place for reflection and remembrance.

8. The Museum

Both Cape Coast and Elmina Castles house museums that provide educational exhibits about the slave trade. These museums play a vital role in preserving history and educating future generations.

9. The Annual Emancipation Day

Ghana commemorates Emancipation Day every year, celebrating the end of slavery and honoring the resilience of those who endured it. Events include ceremonies, reenactments, and educational programs.

The Emotional Toll on Visitors

The legacy of these castles extends beyond their walls, affecting modern Ghanaian society. Understanding these sites helps in comprehending the broader impact of the slave trade on the region

10. The Guided Tours

Guided tours offer detailed accounts of the history and significance of each area within the castles. Knowledgeable guides help visitors understand the full scope of the atrocities committed.

11. The Personal Stories

Hearing personal stories of those who were enslaved adds a human element to the historical facts. These narratives bring the past to life, making the experience more poignant.

12. The Reflection Areas

Designated areas within the castles allow visitors to sit and reflect on what they have seen and learned. These spaces provide a moment of quiet contemplation amidst the heavy history.

Cape Coast Slave Castles in Ghana hold deep historical significance. These structures remind us of the brutal realities of the transatlantic slave trade. Walking through the dark dungeons and narrow passageways, one can almost feel the pain and suffering endured by countless individuals.

These castles are not just historical sites; they are powerful symbols of resilience and the human spirit. Visiting them offers a chance to learn, reflect, and honor those who suffered. It’s a sobering experience that leaves a lasting impact, urging us to remember the past and strive for a better future.

If you ever find yourself in Ghana, take the time to visit Cape Coast Slave Castles. The lessons learned and the emotions felt will stay with you long after you leave.

The BLACK VIKING

Landnámabók (The Book of Settlements) describes Geirmund as “the noblest of all settlers.” According to my Google search the definition of noble means “belonging to a hereditary class with high social or political standing, aristocratic.” It also means “having or showing fine personal qualities, or high moral principles or ideals.” His lineage fits this category but was he a righteous, honourable, good, virtuous, upright human being? You decide.

Landnámabók (The Book of Settlements) describes Geirmund as “the noblest of all settlers.” According to my Google search the definition of noble means “belonging to a hereditary class with high social or political standing, aristocratic.” It also means “having or showing fine personal qualities, or high moral principles or ideals.” His lineage fits this category but was he a righteous, honourable, good, virtuous, upright human being? You decide.

After years of roaming as a Viking, he went to Dublin to meet up with his brother Hamand and his father’s other allies. This famous longphort [2] was a Viking stronghold known for its thriving slave market as well as for other things. At that time the conversation there was all about the need to find another place to hunt the walrus. Ivory was still king and in the regular hunting grounds in northern Russia, the walrus colonies were nearing extinction. Iceland was now on everybody’s mind as the next place to find this “white gold.” Is this what gave him the motivation to sail northward to this small island? Yes, it was. Since there was a great need to find more colonies and since Iceland was where others were thinking of going, he decided to get there first and claim it all.

With him, on his journey northward, Geirmund Heljarskinns brought astonishing wealth, along with armies of men and slaves. First, they sailed around the country to determine where he would find this valuable commodity, this marine species known as the walrus. They soon found huge colonies scattered along the rugged coastline in the Hornstrandir region, but the land was not suitable for human habitation. Once these mammals were discovered he searched for and found a picturesque fjord with land he desired south of the walrus colonies. He set up his estate in Breiðafjörður. As for the walrus, he was quite familiar with hunting them. He had honed his skills during his time in northern Siberia, in Bjarmaland. With his time spent there, he realized great profits, just as his father had before him. From the walrus skins leather rope was made. They extracted its oil, sold the meat, or ate it themselves. The main profit came from their teeth, their incisors known as tusks. African ivory did not arrive in these northern countries until the 14th century, therefore, the walrus tusks remained in great demand for some time. The only ones who could afford such a product were kings or the church. Once his enormous estate was built, he established his routes with stopover points to the hoards of walrus living along the northern coastlines. He had so many men that he could afford to station small armies of slaves in the West Fjords and the Dalir Regions. He would travel with another army of men, easily eighty men at a time, across the land to access this very important commodity. Not even King Harald travelled during peaceful times with more than sixty men. No one in Iceland challenged Geirmund Heljarskinns or even dared to. He controlled a quarter of its land and lived like a king in this country with his huge army ready to protect or kill for him.

Landnámabók (The Book of Settlements) describes Geirmund as “the noblest of all settlers.” According to my Google search the definition of noble means “belonging to a hereditary class with high social or political standing, aristocratic.” It also means “having or showing fine personal qualities, or high moral principles or ideals.” His lineage fits this category but was he a righteous, honourable, good, virtuous, upright human being? You decide.

What do we know about this man? Geirmund was born about 846CE in Avaldsnes, Rogaland, Norway along with his twin brother Hamand. Sons of and Ljufvina Bjarmasdottir, they were said to be ugly with dark skin and Mongolian features. Hence the nickname Heljarskinns, which literally translates as “skin like hell.

Landnámabók (The Book of Settlements) describes Geirmund as “the noblest of all settlers.” According to my Google search the definition of noble means “belonging to a hereditary class with high social or political standing, aristocratic.” It also means “having or showing fine personal qualities, or high moral principles or ideals.” His lineage fits this category but was he a righteous, honourable, good, virtuous, upright human being? You decide.

What do we know about this man? Geirmund was born about 846CE in Avaldsnes, Rogaland, Norway along with his twin brother Hamand. Sons of and Ljufvina Bjarmasdottir, they were said to be ugly with dark skin and Mongolian features. Hence the nickname Heljarskinns, which literally translates as “skin like hell. Their mother, who also had dark skin, was the daughter of the chief or king of Bjarmaland. A cold isolated land in northern Siberia which at the time was teeming with walrus colonies. She is thought to have belonged to an ancient tribe of indigenous people called the Sihirtians. Their legend tells us of a people known to be great hunters and fishermen and thought to have mastered blacksmithing. A people of small stature who had fair hair, light blue eyes, fair skin and lived below the ground. They only came out at night to hunt and fish. They were also thought to have had supernatural powers. Over the centuries though this tribe of peoples was conquered and absorbed into another group of peoples called the Nenets. Eventually, the population of the Sihirtians disappeared as they were integrated into this other group. Their skin became darker and they began to take on the features of this other indigenous group, the Nenets.

King Hjör took Ljufvina to Norway as his wife after negotiating an agreement with her father giving him full access to the trade for their valuable walrus. When the twins were born the father was not present. Disappointed that they did not look like their father, Ljufvina quickly exchanged the twins for a slave boy who was also born at the same time. A fair-haired, blue-eyed child, named Leif who looked more like King Hjör. She thought this would make him happy. A few years later the king expressed disappointment. This boy did not exhibit the strength or intelligence he expected of his own child. Maybe he suspected all along that Leif was not his child, or was it because the poet Brage the old revealed the truth to him and reunited him with his sons? How he found out is immaterial, Ljufvina was left with no choice but to admit to what she had done and to beg for his forgiveness. He could see that she was telling the truth as they had her dark skin and features. It was not long before he realized that both sons had his traits and he accepted them wholeheartedly. They were intelligent, crafty, fierce little warriors. Growing up now with their real father they learned many warrior skills.

Later as a young man Geirmund went Viking and soon established his reputation as a great warrior. With his increasing fame he was headhunted to become part of the Great Heathen Army that invaded England. Through this, he built an even greater legacy and became even more prosperous. In return for his fighting skills, he was gifted land and goods from Guthrum, one of the army’s leaders.

Siberia would not have been an unknown country to him. Between his father and mother, many stories would have been told to both boys. When he was in Siberia is not clear. Was his brother there with him? That too is unknown. But he did apparently spend much time in Bjarmaland where he learned the craft of walrus hunting from his kinsmen and prospered from this commodity adding to his growing affluence and wealth. Unfortunately, at that time the walrus was beginning to be overhunted and the numbers were dwindling. Since the mature female only produced a calf about every three years, the colony's growth rate is slow. And although their life span can be very long, overhunting would certainly have affected the numbers.

At this point, he returned with many slaves and kinsmen from Siberia to Norway only to find his father had lost his land to King Harald. No longer a king of his own land and knowing it was senseless to fight for it against such strength, he left to join up with his brother Hamand and other allies of his father’s living in Dublin. Since Dublin was the centre for the slave trade it was likely that en route to this thriving port, Geirmund would have picked up more slaves in The Northern Isles, Scotland and Ireland and sold them on arrival. After all, business is business. Once there he connected with his brother and his father’s allies. As mentioned previously, the talk was all about the continued demand for the walrus tusk and about locating more hunting grounds. Iceland was becoming the main topic of conversation; it was continually mentioned as a good place to search for these marine mammals. He decided then and there that he would be the one to go to this land before others beat him to this venture. With him, he took the men he already had, a number of slaves, his kinsmen, as well as men from Dublin.

According to Icelandic Roots, he had two women in his life, one from Bjarmaland and the other from Norway. Each one gave birth to a daughter in Iceland. Therefore, at some point, he must have brought them to this country. Whether these two women were with him when he first arrived is unknown, but who did sail with him was a huge group of men who quickly dominated the walrus hunts. He soon controlled a good portion of the land. There is no written account of anyone living there who may have challenged him. Likely he would have been feared by all with such an army of men behind him. He may have lived like a king with great opulence; however, it would have taken a great deal of wealth to maintain that lifestyle, plus feed and cloth such great numbers of people. Also, he would have needed ships, another great expense, to transport this profitable commodity to Dublin. There his brother and their allies would have been the middlemen who sold the ivory to either craftsmen who produced remarkable items for kings and the church, or they would have sold directly to kings, church officials, or merchants from abroad. Those valuable tusks would enhance any treasury or entice any foreign ambassador. Great wealth was amassed by all. With these same ships they would return, possibly bringing his women to him, but it would have brought goods not available in Iceland as well as luxurious items only wealth like his could afford. But was he able to maintain it? According to the website historium.com, when he died in 907CE his friends and family gave him a send-off fit for a king including a ship burial.

It seemed that his lifestyle had not yet been compromised but his family, his kingdom, and his legacy would soon disintegrate. Why? Because sometime during the 900s this mammal disappeared from Iceland. Therefore, his family would have lost their valuable and only commodity: the walrus. Without it how could they possibly maintain their lifestyle as before?

There are questions: Did this great fleet of men decimate those numbers along the Icelandic coastline? Or did this species disappear naturally? Iceland is obviously not a friendly land, their northern shoreline is within the Arctic Circle, harsh and uninviting to both man and beast. Could the volcanic activity it has repeatedly displayed have been responsible? Eruptions have been known to have decimated parts of the land, its people as well as animals repeatedly, but that far north is questionable. The walrus colonies had long since acclimatized themselves to this harsh landscape. No one knows the answer for sure... but the timing fits for man’s intervention. It is very feasible that humans, such as these Northmen, had a hand in making a marine species extinct through overhunting and greed. Geirmund Heljarskinns brought the manpower to Iceland, greedy men who were capable of overhunting just to amass wealth from harvesting their tusks. Never allowing these slow-growing colonies to recuperate to regenerate their numbers. Do his actions indicate “having or showing fine personal qualities, or high moral principles or ideals”? What do you think now, is Landnámabók correct? Was he the “noblest of all settlers”?

Check out this original settler, Geirmund Heljarskinns Halfsson (I566169) in the Icelandic Roots Database. Not only is there a lot of interesting information on his page, but you may find out that you are also related to him. He is 28 times my great-grandfather.

A point of interest: Geirmund’s profile includes a note that quotes the Icelandic author Bergsveinn Bergisson: “...some people have been found in Iceland with mitochondrial DNA of Haplogroup Z1a. Haplogroup Z1a is most often associated with Mongolian and other Asian peoples.” [5] The note continues, "To support his theory, Bergsveinn cites Agnar Helgason's research of the Icelandic gene pool at deCODE and the discovery of a special mutation in the haplogroup Z1a by Dr. Peter Forster at Cambridge University, which confirms the nation's part Mongolian origins. This is still apparent in some Icelanders today, Bergsveinn points out, such as in Björk, who has an Asian look in spite of being ethnically Icelandic." [6]

Civil War, 1861-1865

Jonathan Karp, Harvard University Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, PhD Candidate, American Studies

The story of the Civil War is often told as a triumph of freedom over slavery, using little more than a timeline of battles and a thin pile of legislation as plot points. Among those acts and skirmishes, addresses and battles, the Emancipation Proclamation is key: with a stroke of Abraham Lincoln’s pen, the story goes, slaves were freed and the goodness of the United States was confirmed. This narrative implies a kind of clarity that is not present in the historical record. What did emancipation actually mean? What did freedom mean? How would ideas of citizenship accommodate Black subjects? The everyday impact of these words—the way they might be lived in everyday life—were the subject of intense debates and investigations, which marshalled emerging scientific discourses and a rapidly expanding bureaucratic state. All the while, Black people kept emancipating themselves, showing by their very actions how freedom might be lived.

Self-Emancipation

The Emancipation Proclamation, in 1863, and the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, abolished slavery in the secessionist Confederate states and the United States, respectively, but it is important to remember that enslaved people were liberating themselves through all manners of fugitivity for as long as slavery has existed in the Americas. Notices from enslavers seeking self-emancipated Black people were common in newspapers throughout the Americas, as seen in this 1854 copy of the Baltimore Sun.

The question of how formerly enslaved people would be regarded by and assimilated into the state as subjects was most obviously worked out through the Freedmen’s Bureau, which was meant to support newly freed people across the South. Two years before the Bureau was established, however, there was the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission. Authorized by the Secretary of War in March 1863, the Inquiry Commission was called in part as a response to the ever-increasing number of refugees—who were still referred to at the time as “contraband”—appearing at Union camps. The three appointed commissioners—Samuel Gridley Howe, James McKaye, and Robert Dale Owen—were charged with investigating the condition and capacity of freedpeople.

Historians are still working to understand the scale of refugees’ movements during the Civil War. Abigail Cooper estimates that by 1865 there were around 600,000 freedpeople in 250 refugee camps. Many of the camps were overseen by the Union, while others were established and run by freedpeople themselves. Conditions in the camps could be brutal. In 1863, the Inquiry Commission heard that 3,000 freedmen had fortified the fort in Nashville for fifteen months without pay. Rations were slim. In spite of these conditions, the camps were also sites where Black people profoundly restructured the South by their very movement and relationships.

Port Royal Experiment

During the Civil War, the U.S. government began an experiment in the Sea Islands of South Carolina. Plantation owning enslavers had abandoned their lands, leaving behind over 10,000 formerly enslaved Black people. With the help of abolitionist charities from the North, these Black farmers cultivated cotton for wages in the same places they had formerly been held in bondage. Their work was so successful that it inspired international calls for support, like this letter published in Manchester, England. The short-lived success of this experiment was largely ended at the government's hands, when the lands were returned to White ownership.

The Inquiry Commission, a large portion of whose records are held at Harvard, focused many of their efforts on the camps. It was not clear how, exactly, they should go about their work. The Commission was established before the field of sociology emerged with its institutionalized tools for the supposedly scientific study of populations. A federal body had never before been responsible studying people who were or had been enslaved. The commissioners travelled across the American South and Canada, observing and interviewing freedmen. They sent elaborate surveys to military leaders, clergy, and other White people who interfaced with large numbers of people who had escaped slavery. Through this work, the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission made Black people into subjects of the United States’ scientific gaze. Their records are an invaluable record of life under slavery; they also reinscribed underlying racial logics.

The Inquiry Commission, a large portion of whose records are held at Harvard, focused many of their efforts on the camps. It was not clear how, exactly, they should go about their work. The Commission was established before the field of sociology emerged with its institutionalized tools for the supposedly scientific study of populations. A federal body had never before been responsible studying people who were or had been enslaved. The commissioners travelled across the American South and Canada, observing and interviewing freedmen. They sent elaborate surveys to military leaders, clergy, and other White people who interfaced with large numbers of people who had escaped slavery.

Through this work, the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission made Black people into subjects of the United States’ scientific gaze. Their records are an invaluable record of life under slavery; they also reinscribed underlying racial logics.

Slavery, Abolition, Emancipation, and Freedom has a collection of 189 objects related to the Commission’s inquiry. The vast majority of them are responses to their survey, written by White people the Commission identified as having special knowledge of freedmen. The view of slavery from this vantage point is limited. Most if not all of the respondents recount conversations with people who were or had been enslaved, but these accounts are all mediated by their authors and the Commissioners. There’s no telling what the quoted enslaved people would or wouldn’t have shared with these people, or why. If some shape of life under slavery emerges from reading these survey responses, it is a necessarily distorted one. The American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission is emblematic of a style of scientific discourse that set its sights on Black people and the cultural meanings of race without concern for the views of Black people. In this field, Whiteness was necessary for expertise.

The surveys are most revealing as records of how these agents of the federal government conceived of the question of freedom—what they called, “one of the gravest social problems ever presented a government.” What kinds of questions did they ask? The forms had forty-two questions. Some asked for geographic and population data. Others asked for information about life before emancipation: did freedmen carry signs of previous abuse (they did) and did their masters have an effect on enslaved peoples’ families (they invariably did)? The vast majority of the questions, however, asked for the respondent’s opinions and general observations of the formerly enslaved refugees. The Commission wanted to know about these peoples’ strength, endurance, intellectual capacity, attachments to place, as well as their religious devotion, their general disposition, work ethic, and ways of domestic life. The list ended with the most important question, which the previous ones had apparently prepared the respondent to answer to the best of their abilities: “In your judgement are the freedmen in your department considered as a whole fit to take their place in society with a fair prospect of self-support and progress or do they need preparatory training and guardianship? If so of what nature and to what extent?”

the internet developed

by Philip Emeagwali

Philip Emeagwali (born August 23, 1954) is a Nigerian American computer scientist. He achieved computing breakthroughs that helped lead to the development of the internet. His work with simultaneous calculations on connected microprocessors earned him a Gordon Bell Prize, considered the Nobel Prize of computing.

early life in africa

Born in Akure, a village in Nigeria, Philip Emeagwali was the oldest in a family of nine children. His family and neighbors considered him a prodigy because of his skills as a math student. His father spent a significant amount of time nurturing his son's education. By the time Emeagwali reached high school, his facility with numbers had earned him the nickname "Calculus."

Fifteen months after Emeagwali's high school education began, the Nigerian Civil War erupted, and his family, part of the Nigerian Igbo tribe, fled to the eastern part of the country. He found himself drafted into the army of the seceding state of Biafra. Emeagwali's family lived in a refugee camp until the war ended in 1970. More than half a million Biafrans died of starvation during the Nigerian Civil War.

After the war ended, Emeagwali doggedly continued to pursue his education. He attended school in Onitsha, Nigeria, and walked two hours to and from school each day. Unfortunately, he had to drop out due to financial problems. After continuing to study, he passed a high school equivalency exam administered by the University of London in 1973. The education efforts paid off when Emeagwali earned a scholarship to attend college in the U.S.

Emeagwali traveled to the U.S. in 1974 to attend Oregon State University. Upon arrival, in the course of one week, he used a telephone, visited a library, and saw a computer for the first time. He earned his degree in mathematics in 1977. Later, he attended George Washington University to earn a Master of Ocean and Marine Engineering. He also holds a second master's degree from the University of Maryland in applied mathematics.

While attending the University of Michigan on a doctoral fellowship in the 1980s, Emeagwali began work on a project to use computers to help identify untapped underground oil reservoirs. He grew up in Nigeria, an oil-rich country, and he understood computers and how to drill for oil. Conflict over control of oil production was one of the critical causes of the Nigerian Civil War.

computing achievements

Initially, Emeagwali worked on the oil discovery problem using a supercomputer. However, he decided it was more efficient to use thousands of widely distributed microprocessors to do his calculations instead of tying up eight expensive supercomputers. He discovered an unused computer at the Los Alamos National Laboratory formerly used to simulate nuclear explosions. It was dubbed the Connection Machine.

Emeagwali began hooking up over 60,000 microprocessors. Ultimately, the Connection Machine, programmed remotely from Emeagwali's apartment in Ann Arbor, Michigan, ran more than 3.1 billion calculations per second and correctly identified the amount of oil in a simulated reservoir. The computing speed was faster than that achieved by a Cray supercomputer.

Describing his inspiration for the breakthrough, Emeagwali said that he remembered observing bees in nature. He saw that their way of working together and communicating with each other was inherently more efficient than trying to accomplish tasks separately. He wanted to make computers emulate the construction and operation of a beehive's honeycomb.

Emeagwali's primary achievement wasn't about oil. He demonstrated a practical and inexpensive way to allow computers to speak with each other and collaborate all around the world. The key to his achievement was programming each microprocessor to talk with six neighboring microprocessors simultaneously. The discovery helped lead to the development of the internet.

Emeagwali's work earned him the Institute of Electronics and Electrical Engineers' Gordon Bell Prize in 1989, considered the "Nobel Prize" of computing. He continues to work on computing problems, including models to describe and predict the weather, and he has earned more than 100 honors for his breakthrough achievements. Emeagwali is one of the most prominent inventors of the 20th century.

Jesse Eugene Russell: The Visionary Behind the Cellular Revolution

Jesse Eugene Russell is a name that should echo through the halls of technological history. An African American engineer and inventor, Russell’s revolutionary work transformed the way we communicate, laying the groundwork for the wireless world we inhabit today. His contributions have earned him a rightful place as a pioneer of digital connectivity.

early life and Education

Born in Nashville, Tennessee, Russell displayed an insatiable curiosity and aptitude for engineering from a young age. He went on to earn his Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering from Tennessee State University, a historically Black university. His academic excellence led him to Stanford University, where he achieved his Master of Science in Electrical Engineering.

Russell’s career truly began to take flight when he joined AT&T Bell Laboratories. It was here that his groundbreaking ideas began to take shape. In an era dominated by landline phones, Russell envisioned a world where communication was untethered, where people could connect on the move.

His relentless pursuit of this vision led him to develop the architecture for modern cellular communication. Russell’s innovations in digital signal processing, radio technology, and network design were fundamental to creating the foundation upon which wireless networks now operate.

While Russell’s technical brilliance is undeniable, his philosophy towards digital connectivity was equally transformative. He firmly believed that the benefits of wireless technology shouldn’t be confined to the privileged few, but should be accessible to people from all walks of life.

This sense of inclusivity was central to Russell’s work. He championed the idea that cellular technology could bridge divides, empower communities, and bring vital information to those who needed it most, regardless of socioeconomic background.

The impact of Jesse Eugene Russell’s work cannot be overstated. Billions of people around the planet rely on the cellular networks his innovation made possible. The smartphone revolution, the rise of telemedicine, and the vast potential of 5G and beyond — all trace their roots back to Russell’s vision.

In recognition of his contributions, Russell has been inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame and the National Academy of Engineering. He has received numerous awards, including the prestigious National Medal of Technology and Innovation.

Who Was Daniel Hale Williams?

Daniel Hale Williams pursued a pioneering career in medicine. An African American doctor, in 1891, Williams opened Provident Hospital, the first medical facility to have an interracial staff. He was also one of the first physicians to successfully complete pericardial surgery on a patient. Williams later became chief surgeon of the Freedmen’s Hospital.

early life

Daniel Hale Williams III was born on January 18, 1856, in Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania, to Sarah Price Williams and Daniel Hale Williams II. The couple had several children, with the elder Daniel H. Williams inheriting a barber business. He also worked with the Equal Rights League, a Black civil rights organization active during the Reconstruction era.

More From BiographyThe Rise and Fall of Oppenheimer

After the elder Williams died, a 10-year-old Daniel was sent to live in Baltimore, Maryland, with family friends. He became a shoemaker’s apprentice but disliked the work and decided to return to his family, who had moved to Illinois. Like his father, he took up barbering, but ultimately decided he wanted to pursue his education. He worked as an apprentice with Dr. Henry Palmer, a highly accomplished surgeon, and then completed further training at Chicago Medical College.

Williams set up his own practice in Chicago’s South Side and taught anatomy at his alma mater, also becoming the first African American physician to work for the city’s street railway system. Williams — who was called Dr. Dan by patients — adopted sterilization procedures for his office informed by the recent findings on germ transmission and prevention from Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister.

Due to the discrimination of the day, African American citizens were still barred from being admitted to hospitals and Black doctors were refused staff positions. Firmly believing this needed to change, in May 1891, Williams opened Provident Hospital and Training School for Nurses, the nation’s first hospital with a nursing and intern program that had a racially integrated staff. The facility, where Williams worked as a surgeon, was publicly championed by famed abolitionist and writer Frederick Douglass.

.jpg)

Completes Open-Heart Surgery

In 1893, Williams continued to make history when he operated on James Cornish, a man with a severe stab wound to his chest who was brought to Provident. Without the benefits of a blood transfusion or modern surgical procedures, Williams successfully sutured Cornish’s pericardium, the membranous sac enclosing the heart, thus becoming one of the first people to perform open-heart surgery. (Physicians Francisco Romero and Henry Dalton had previously performed pericardial operations.) Cornish lived for many years after the operation.